Despite federal and state laws designed to protect their rights, persons with disabilities (PWDs) in Sokoto state still face significant barriers to healthcare. An investigation by The Liberalist reveals that most health facilities lack basic accessibility features, effectively excluding many from essential treatment. With the 2024 accessibility deadline now passed, Sokoto’s failure to implement the law highlights persistent neglect and deep inequalities in the state’s health system.

_____________

In March 2025, Hassan Musa awoke feeling cold and shivering, before his temperature suddenly soared to a dangerous level. The fever was accompanied by profuse sweating and a throbbing headache. Musa, a 54-year-old wheelchair user, soon experienced severe body aches that made even simple movements, such as sitting upright, painfully difficult.

Within minutes, his condition worsened. He appeared pale, restless, and dehydrated from continuous sweating. Musa spent most of that morning lying down, unable to eat and occasionally battling dizziness. As he struggled to summon the strength to seek help, the pain overwhelmed him until one of his brothers arrived to take him to the hospital. He was lifted helplessly and seated between his brother and a motorcycle rider for the journey to Gidan Hamma Primary Health Centre (PHC).

The facility, located just a few minutes from Musa’s home in Gidan Hamma, a remote village in Wamako Local Government Area of Sokoto state, became his only hope for relief. There, the two men supported him in the consulting room, where he was diagnosed with malaria. Musa received treatment, rested briefly to ease the pain, and was advised to return the following day for further care.

The next morning, determined to continue his treatment, Musa wheeled himself to the facility, only to face a new ordeal. His handcycle wheelchair could not fit through the bumpy, narrow entrance. Fortunately, two men nearby came to his aid and carried him inside. Yet even then, the consulting room was inaccessible, and the same men had to lift him in once more.

“It was my first time going to the facility on my own, and the experience was torturous and embarrassing,” Musa recalled, shaking his head. “I couldn’t enter the facility with my handcycle wheelchair, and imagine if no one had been around to help me.”

Hassan Musa with his handcycle wheelchair. Credit: Shereefdeen Ahmad

Unable to complete his treatment, Musa decided not to return. “I didn’t complete the treatment, and since then, I’ve avoided anything that would take me back to that facility,” he told The Liberalist.

A visit to the Gidan Hamma PHC confirmed Musa’s concerns. The building lacks ramps, making it impossible for wheelchair users and others with mobility impairments to move freely. This contravenes the Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act, 2018, which guarantees equal access to healthcare and mandates that all public buildings, including health facilities, comply with accessibility standards such as ramps, tactile signage, accessible washrooms, and other inclusive features.

Facilities are also required to provide sign language interpreters, braille, and large-print materials for patients with visual impairments. Yet for Musa and many others, even basic access remains out of reach. Almost all entrances at the facility, including toilets, consulting rooms, and wards, are inaccessible to individuals using wheelchairs.

Entrance to the consulting room in Gidan Hamma PHC. Credit: Shereefdeen Ahmad

The building’s entrance consists of three uneven, cracked concrete steps leading up to a raised veranda, where the plaster has peeled away along the edges. The structure shows clear signs of neglect, with eroded sections and no ramps or support railings, making it inaccessible to people with disabilities or anyone with mobility challenges.

Entrance of Gidan Hamma PHC. Credit: Shereefdeen Ahmad

A staff member at the facility, who requested anonymity, told The Liberalist that the situation is further compounded by the lack of an ambulance for emergency referrals. “We do not have an ambulance to refer patients in critical condition. Also, as you can see,” he said, pointing towards the entrance, “it is not only inaccessible to persons with disabilities, but even the elderly struggle to use it. It completely excludes both people with disabilities and other vulnerable groups.”

Section 6 of the Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act, 2018 provides a five-year transitional period, from 2019, for all public buildings to become accessible. That deadline expired in 2024. Yet, the situation at Gidan Hamma PHC and other health centres in Sokoto shows that compliance remains largely ignored.

Ten Facilities, One Pattern of Exclusion

An on-site assessment of ten primary healthcare facilities across five local government areas (LGAs) in Sokoto state paints a grim picture. Facilities such as Rinin Tawaye PHC in Sokoto North LGA, Mana Babba PHC in Sokoto South LGA, Dundaye Health Clinic, Gidan Tudu Health Post, and Bakin Gulbi Health Clinic in Wamako LGA; Bagida Health Post and Gesalode Health Post in Tambuwal LGA; as well as Ginjo Health Post, Mongoho PHC, and Ruwa Wuri PHC in Tangaza LGA, all share the same problem: no signage, no wheelchair access, narrow doorways, internal steps, no sign language interpreter, no railings, and inadequate toilets.

These infrastructural gaps effectively exclude persons with disabilities (PWDs) from accessing healthcare, deepening existing inequalities and undermining their rights to effective and dignified health services.

According to the World Health Organisation’s World Disability Report (2011), about 15 percent of Nigeria’s population, roughly 25 million people, live with disabilities. More recent figures from the National Commission for Persons with Disabilities (NCPWD) estimate that number at around 35.1 million Nigerians.

While exact data for Sokoto state are not available, government records indicate that at least 69,979 PWDs received financial support from the state government within one year, while another report noted that 13,000 beneficiaries receive monthly stipends. Despite these efforts, basic accessibility in health facilities remains largely unaddressed.

Sokoto, however, is only a microcosm of a much larger national crisis. A report on disability inclusion in Nigeria revealed that 28 percent of health facilities nationwide lack basic accessibility features for persons with disabilities. It assessed progress since the enactment of the law in 2019 and found that while legislative frameworks exist, implementation remains weak. “Public spaces remain largely inaccessible,” the report noted. “The 5% employment quota for persons with disabilities remains unenforced, mainly due to persistent workplace discrimination. 28% of health facilities lack basic accessibility features, creating significant barriers to essential services.”

The report ranked Sokoto state 11th nationally, with a 44 percent disability inclusion score, indicating moderate progress. However, healthcare inclusion remains limited, with facilities only 40 to 50 percent accessible, few trained service providers, and inadequate infrastructure for wheelchair users and individuals with developmental disabilities.

Dundaye Health Clinic. Credit: Shereefdeen Ahmad

Law Without Implementation

Although the Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act is a federal law, its enforcement depends largely on the willingness of individual states to domesticate it.

“Under Nigeria’s federal system, health and social welfare fall within the jurisdiction of the states. This means that each state must enact its own version of the law to make it legally enforceable at the local level,” explained Mujeeb Abdulwasiu, a Lagos-based legal practitioner.

So far, 23 states have enacted disability laws, while 15 have established implementing agencies. Sokoto is among the 23 states that have passed their own legislation, the Sokoto State Prohibition of Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities Law, 2021. However, implementation at the local level remains sluggish, with little evidence of enforcement or compliance.

Infographic on disability inclusion in Nigeria and Sokoto. Credit: Shereefdeen Ahmad

Barrister Mujeeb noted that “legal and policy reforms, such as the establishment of complaint units and the provision of resources to pursue legal action, are urgently needed to bridge the gap between the rights guaranteed in disability laws and the lived experiences of persons with disabilities seeking healthcare.”

In Sokoto, despite the domestication of the law, gaps in institutional capacity and weak enforcement continue to deny people like Musa equal access to essential services.

PWDs Still Waiting for Change

For Mukhtar Sani, General Secretary of the Joint National Association of Persons with Disabilities (JONAPWD), Sokoto chapter, the situation remains dire.

“Honestly speaking, health facilities in the state are not accessible at all,” he lamented. “In terms of healthcare, there has been no improvement, it remains one of our major challenges.”

Sani added that in many clinics, the absence of sign language interpreters and the lack of accessible structures continue to discourage persons with disabilities from seeking care.

“The law is there, but the major challenge is implementation,” he said. “When the law was domesticated in 2021 and later amended in 2023, one of the key recommendations was to establish the Sokoto Commission for Persons with Disabilities. However, after the amendment, it was downgraded to an agency under the Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs and Social Welfare.”

He also expressed concern about the lack of representation in decision-making. “One of the ironic things is that the government’s special adviser on disability matters is a person without a disability,” he said. “The marginalisation is still there. We have been advocating that a person with a disability should occupy that office because nothing about us should happen without us.”

Signposts in Dundaye Health Clinic. Credit: Shereefdeen Ahmad

In an interview with The Liberalist, Alhaji Aminu Bello, the Director of Social Welfare at the Sokoto state Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs and Social Welfare, said the ministry’s role is limited to handling the monthly stipends for persons with disabilities. “Other matters outside the payment are handled by the office of the special adviser to the government on persons with disabilities,” he added.

Meanwhile, when contacted, Aliyu Umaru, the Sokoto state Special Adviser on Physically Challenged/Disabled Matters, said he could not grant an interview via phone call unless this reporter visited his office in person, even if represented by someone. He asked the reporter to call back to schedule an appointment.

After several follow-up calls over two days to arrange the interview, Mr. Umaru said, “you are disturbing me. I cannot share the government’s plans with someone I don’t know unless you come physically.” When the reporter explained that the call was to schedule the in-person interview, as he had earlier requested, he replied, “I can only grant an interview after seeking approval from the Secretary to the State Government. After that, I will get back to you.”

As of the time of filing this report, Mr. Umaru had yet to respond.

In the meantime, despite the existence of both federal and state laws protecting their rights, persons with disabilities in Sokoto continue to face exclusion from healthcare facilities meant to serve them.

No Way Home for Musa

As Musa grew increasingly discouraged from seeking treatment at the Gidan Hamma PHC, his only alternative became private clinics. But this option remains a distant dream and a costly luxury for him.

“I only went to the private clinic for treatment once,” Musa recalled. “The money is too much for a person like me to afford every time. It cost over ₦3,000.”

Musa’s struggle is far from unique. Reports show that Sokoto state’s multidimensional poverty rate stands at about 90.5 percent, according to the 2022 National Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). This implies that roughly nine out of every ten residents in the state live in multidimensional poverty, deprived in areas such as health, education, and standard of living. Although the state government has questioned the methodology of the report, the figures still reveal the deep structural poverty affecting households across the region.

Ruwa Wuri PHC. Credit: Shereefdeen Ahmad

For persons with disabilities like Musa, the reality is even harsher. Studies indicate that over 90 percent of Nigerians with disabilities live in poverty, with about 80 percent of women with disabilities reporting experiences of sexual abuse. The report also noted that healthcare costs create insurmountable barriers for most people within the disability community, further excluding them from accessing quality medical care.

A Heavy Price for Poverty and Neglect

Betrayed by a broken healthcare system and constrained by poverty, Musa now mostly relies on traditional herbs to treat malaria, a disease that continues to thrive in Sokoto state.

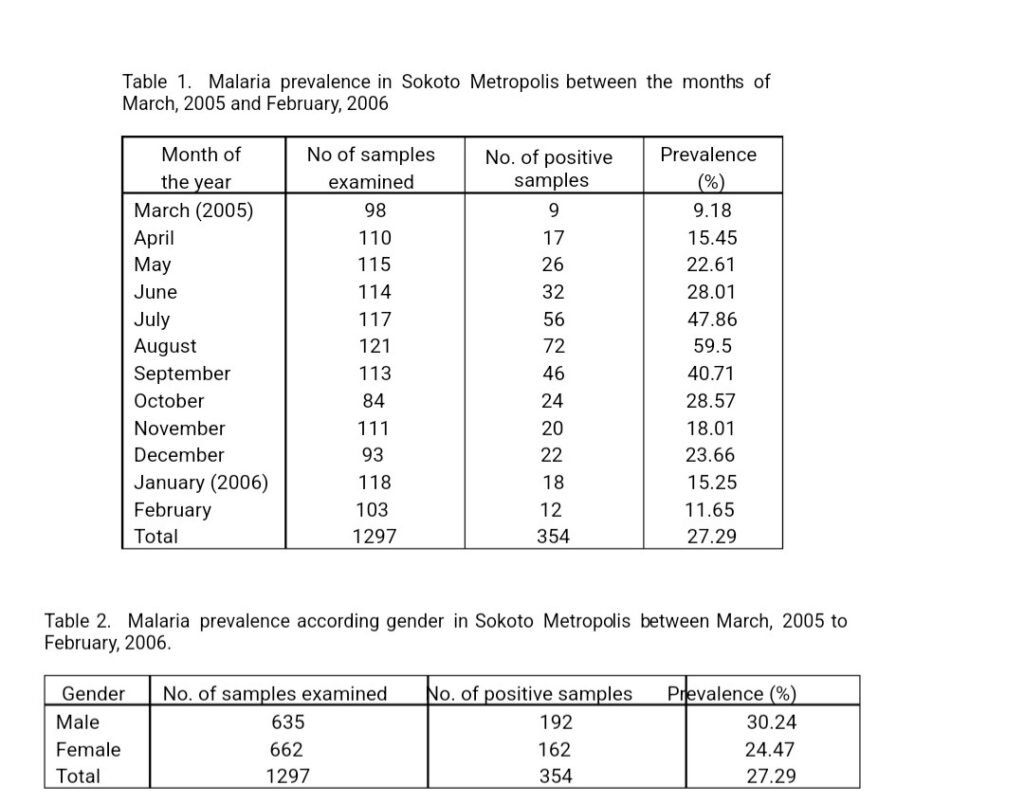

For years, the state has remained one of Nigeria’s malaria hotspots. Despite progress, prevalence rates remain high. In 2015, malaria prevalence in Sokoto stood at 46.6 percent, one of the highest in the country. A 2021 study later showed a decline to 35.9 percent, yet the disease continues to pose major challenges, especially in rural communities with poor access to healthcare facilities.

A report by the National Malaria Elimination Programme (NMEP) listed Kebbi, Zamfara, and Sokoto states among those with the highest malaria prevalence in Nigeria. The situation worsens during the rainy season, according to Pharmacist Adamu Anas of Rahusa Pharmaceutical in Sokoto. “Every day, about 20 people come to our pharmacy with malaria complaints,” he said, highlighting the persistent burden of the disease across the state.

Tables showing malaria prevalence in Sokoto metropolis. Source/credit: African Journal of Biotechnology Vol. 8 (24), pp. 7101-7105, 15 December, 2009

Malaria remains one of the world’s most devastating tropical diseases. Studies estimate that it affects about 247 million people annually among the 3.3 billion at risk globally, resulting in nearly a million deaths each year, mostly among children under five. Nearly 90 percent of these deaths occur in Sub-Saharan Africa, making malaria the leading cause of under-five mortality in the region.

The 2022 World Malaria Report shows Nigeria’s share of the global malaria burden is 27 percent of all malaria cases and 31 percent of global malaria deaths. Within West Africa, Nigeria alone is responsible for an estimated 55 percent of malaria cases, a staggering indication of the disease’s continued grip on the nation.

Poor Funding and Policy Gaps Undermine Progress

Recognising the challenge, the Sokoto state government, in partnership with development and health agencies, has launched several initiatives to tackle malaria. Among them is the establishment of the Sokoto state Malaria Elimination Control Agency, reportedly the first of its kind among Nigerian states. The agency is tasked with coordinating malaria prevention and treatment programmes across the state.

However, these efforts appear limited in scope, as health facilities remain physically inaccessible to certain groups of citizens. The absence of inclusive structures such as ramps, wide doorways, and accessible consulting rooms continues to alienate persons with disabilities like Musa, undermining the government’s public health commitments. The gap between policy and implementation signals institutional neglect of disability inclusion within the state’s health system.

Bagida Health Post. Credit: Shereefdeen Ahmad.

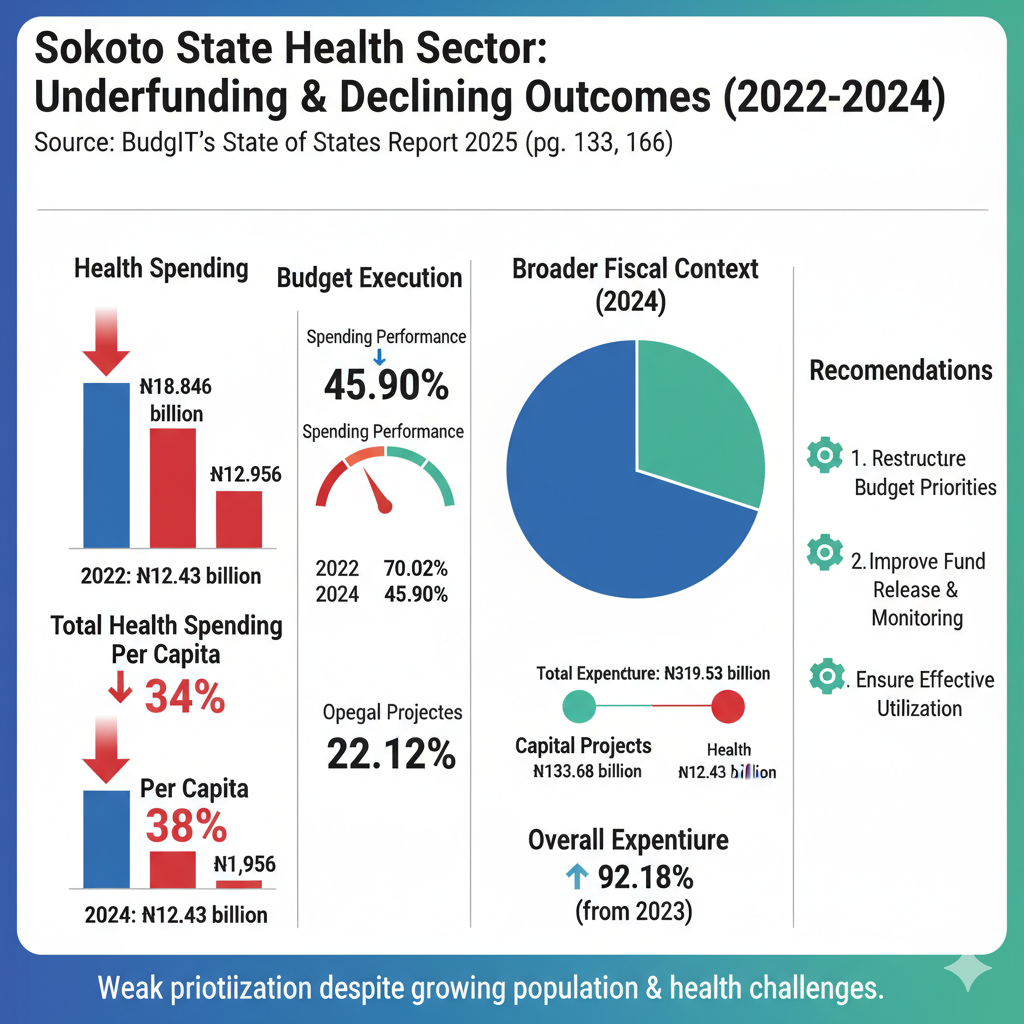

According to BudgIT, a civic tech non-profit organisation, Sokoto state’s allocation and performance in the health sector reveal significant underfunding and declining outcomes over the past three years. The state’s total health spending fell sharply from ₦18.83 billion in 2022 to ₦12.43 billion in 2024, marking a reduction of over 34 percent. Similarly, its health spending per capita declined from ₦3,146 in 2022 to ₦1,956 in 2024, while spending performance (a measure of budget execution) dropped from 70.02 percent to 45.90 percent in the same period. This steady decline signals weak prioritisation of health financing despite the growing population and persistent public health challenges, such as malaria, in the state.

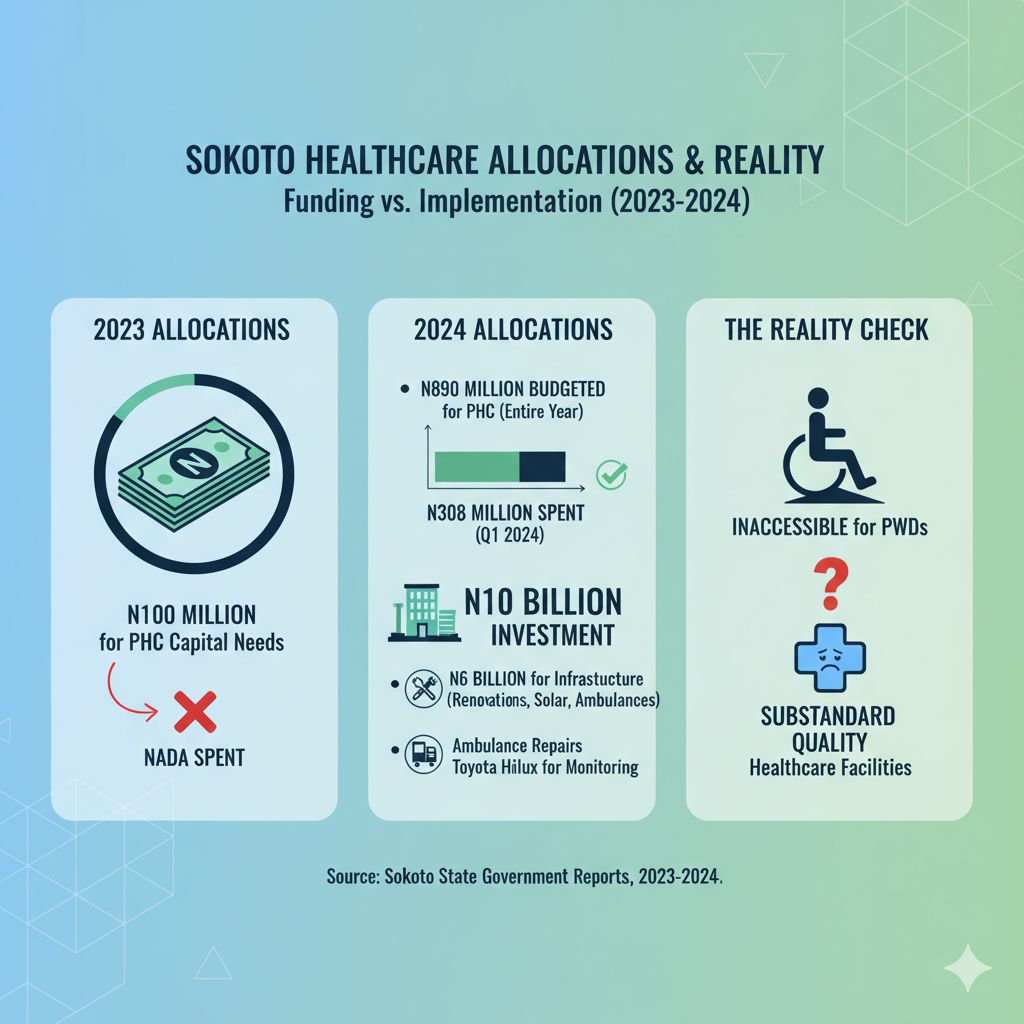

In 2023, the Sokoto state government allocated N100 million for the capital needs of PHCs, yet not a single naira was spent. By the first quarter of 2024, only N308 million out of the N890 million earmarked for PHCs for the entire year had been utilized.

In 2024, the government announced a N10 billion investment to renovate, refurbish, and equip 244 PHCs across the 23 local government areas. Of this amount, over N6 billion was allocated to infrastructure improvements, including the installation of solar-powered lighting, ambulance repairs, and the procurement of a Toyota Hilux for monitoring and supervision.

However, despite these allocations, many health facilities remain inaccessible to PWDs and fall far short of the standards for quality healthcare delivery.

Infographic showing Sokoto state’s allocations and reality for PHCs. Credit: Shereefdeen Ahmad

In the broader fiscal context, Sokoto’s total expenditure for 2024 stood at ₦319.5 billion, reflecting a 92.18 percent increase from the previous year. Of this, ₦133.68 billion was dedicated to capital projects while ₦120.39 billion went to operating expenses. Yet, despite this strong overall fiscal growth, the health sector’s share remained modest and poorly executed. The report recommends that the state government restructure its budget priorities, improve fund release and monitoring mechanisms, and ensure that allocations to health are effectively utilized to enhance service delivery outcomes and meet the state’s developmental goals.

Infographic showing Sokoto state’s health sector spending. Credit: Shereefdeen Ahmad

When contacted, Dr. Faruq Abubakar, the Sokoto state Commissioner for Health, declined to comment on the findings, stating that the Sokoto State Primary Health Care Development Agency (SPHCDA) is the appropriate body to address the matter.

Meanwhile, when The Liberalist contacted Larai Aliyu, the Executive Secretary of the SPHCDA, he did not respond to multiple calls and messages sent to her phone.

Musa Is Not Alone

Each day Musa lives with the resignation of knowing that the healthcare system meant to protect him remains out of reach by law and neglect.

But he is not alone. Nura Aliyu, a 28-year-old man with hearing impairment, shares a similar ordeal at Bakin Gulbi Health Clinic. The absence of sign language interpreters and proper signage further alienates him from accessing medical care at the facility.

Entrance of Bakin Gulbi Health Clinic. Credit: Shereefdeen Ahmad

For persons with hearing disabilities, both the Act and the Sokoto state Prohibition of Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities Law 2021 mandate that health centres should provide sign language interpreters, and written communication tools to facilitate effective communication during medical visits.

Section 22 of the law provides that health facilities “where a person with communicational disabilities is medically attended to shall make provision for special communication.”

However, none of the health facilities visited in the state met these requirements.

Nura faces significant challenges due to the lack of interpreters. Communicating his experience through a community interpreter, he said, “as someone who is constantly battling with malaria, I know the facility does not have a sign language interpreter.

So, there’s no need to go there for treatment unless I go with someone who can explain to the doctor.”

A staff member of the facility, who requested anonymity for fear of victimisation, confirmed Nura’s concerns.

“It sometimes gets frustrating when you can’t understand each other,” the staff member admitted. “You can’t blame us for getting annoyed with hearing-impaired people sometimes. The government is supposed to make provisions to cater for persons with such disabilities. It’s not a requirement that we, the staff members, must understand sign language.”

Beyond the absence of interpreters, the facility itself is not accessible. Like Gidan Hamma PHC, the entrance features worn concrete steps leading up to a raised veranda with visible cracks and peeling plaster along the base. There are no ramps or railings, making entry difficult for persons with mobility challenges or the elderly. The toilets are equally inaccessible, with doors too narrow for wheelchair users.

Toilets in Bakin Gulbi Health Clinic. Credit: Shereefdeen Ahmad

The same situation persists at Dundaye Health Clinic, Ruwa Wuri PHC, Mongoho PHC, and other facilities across the state.

Haruna (surname withheld), a 26-year-old man with speech impairment, said he detests going to Mongoho PHC for medical care because of the ridicule he faces.

“Whenever I begin to speak and stutter, even the staff members giggle and sometimes openly laugh at me,” he said. “This has discouraged me from visiting the facility most times, just to avoid being mocked.”

Section 19 of the Sokoto State Prohibition of Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities Law 2021 states that the government must guarantee that persons with disabilities have unfettered access to adequate health care without discrimination on the basis of disability.

However, despite the existence of both federal and state disability laws, stories like those of Haruna, Musa, and Nura highlight the deep lack of disability inclusion in Sokoto’s healthcare system, further worsening existing inequalities such as unemployment and discrimination that persons with disabilities face daily.

“The Sokoto state government should enforce the accessibility standards across all health facilities to ensure persons with disabilities can access care,” said Dr Aminu Magashi, a Health Economist and Coordinator at Africa Health Budget Network (AHBN). “Health funding must be increased and protected, with allocations tied to measurable inclusion outcomes.”

He added that healthcare workers should also receive training in disability-sensitive service delivery, including basic sign language skills.

“Persons with disabilities should be appointed to decision-making roles within the health sector to ensure inclusive policies. Finally, an independent state monitoring mechanism should be established to regularly audit accessibility compliance in all health facilities.”