Under a patch of semi-shade, Fatima Abdullahi, 36, pulled her child closer against the afternoon heat. She remembered vividly the night of July 16, 2025. Her body temperature climbed until she could no longer catch her breath. She fainted and woke up drenched in water; a circle of women fanned her with tired hands.

As she spoke, she fought to remain composed. She punctuated her story with long silences, a deliberate effort to keep her tears from breaking through.

“I have never been used to heat. I can hardly breathe when the heat is too much. I feel the intensity of the heat so much during the day here. It feels like my body is on fire. I feel the same way sometimes at night as well which was what led to the fainting. Sometimes the weather can be so hot it feels as though I am being squeezed into a tight place,” she told The Liberalist.

Fatima, a nursing mother, has lived in Magaji Dawaki Primary School for five years. She is among the survivors who fled to Sabon Birni as armed insurgency and rural violence surged across northwest Nigeria. The town is located on the border with the Republic of Niger, sharing proximity with Zamfara State to its east and Kebbi State to the west.

Fatima told The Liberalist she walked from Garki village for days with others from Yobe, Zamfara, and Kebbi states. With no formal settlement plan at Sabon Birni, displaced families began occupying public schools, motor parks, and abandoned buildings. These spaces were never designed for habitation.

As of 2025, the presence of armed non-state groups in Sabon Birni has heightened insecurity. Residents in informal sites, including Abdulhamid Primary School, 30 Housing, Magaji Dawaki Primary School, Gidan Sardauna, Model Primary School and Colombia Motor Park, say they live in constant fear of attacks. Sabon Birni is now one of at least seven areas in Sokoto under frequent attack by terror groups known locally as bandits. In May 2020, over 74 people were killed in multiple attacks across the district.

Beyond the violence, survivors in the camps lack access to basic needs. Many can hardly afford a single meal per day. They live without electricity or proper health services and must trek long distances to get clean water.

“We suffer a lot. The bandits chased us out of our homes and we ended up here in a very tight condition. We don’t have a conducive sleeping space. There are more than fifty people in a room. Our families are also scattered all around the camp due to limited space. My husband is in a different place, some of the kids are also in a separate place while myself and some of the kids are here,” Fatima said.

Fatima and other displaced women said they struggled to survive extreme heat so suffocating, sometimes, it felt like dying.

“You can imagine how hot it is to be in such a place. Sometimes, the heat can be so unbearable it feels like dying. This place is not like home. My health is now fragile, our living condition is bad, I have lost weight and we live in constant fear. We feel the strongest heat in the afternoon and at night. Neither of us can afford a fan,” she said.

Sokoto is a very hot and dry area. Research shows it has an average daytime temperature above 40 °C for most times of the year. According to the Nigerian Meteorological Agency (NiMeT), Nigeria’s average annual temperature increased by approximately 1.2°C over the past century. However, the rate of warming has accelerated, rising by nearly 1.4°C since the early 2000s alone.

While extreme heat events were rare in the 1980s, the 2020s have seen multiple severe heatwaves annually. In 2024, temperatures in Sokoto, Maiduguri, and Yola exceeded 47°C, marking some of the highest levels ever recorded in Nigeria.

Experts say Nigeria is a climate change hotspot, leaving the country particularly vulnerable to the intensifying frequency and intensity of heat-related conditions. Figures from the Federal Ministry of Health show a 20% year-on-year increase in heat-related cases in 2023. That trend accelerated in 2024, with cases rising 30% and more than 2,000 deaths attributed to extreme heat.

Medical experts say the surges have led to increased incidents of heatstroke and dehydration while also exacerbating chronic cardiovascular and respiratory conditions among the population.

The heat is also fueling a secondary crisis in the energy sector. As citizens turn to cooling systems to cope with the weather, electricity demand has surged, frequently overwhelming the national grid.

The Nigerian Electricity Regulatory Commission (NERC) reported that power demand rose 25% during the 2023 heatwave and jumped by 30% in 2024. The spike in consumption has led to frequent outages, disrupting both domestic life and commercial activity in Africa’s most populous nation.

Adapting to Heat Stress Cooling Systems

Baraka Shuaibu, a 29-year-old pregnant woman living in the displacement camp, described how she struggles to cope with extreme heat whenever temperatures reach record highs.

“I cool myself with water. On some days, I bathe like five times a day. There is no electricity nor do we have fans. The effect of the heat is really bad and it is usually worse in some months. Now you can see everyone, including the kids visibly distressed and bathing rarely helps. The bathrooms are exposed which makes it uncomfortable. Also, due to our culture a woman cannot expose her body to receive fresh air. She has to be covered since we are not at home, hence no privacy but a man can be on shorts. Also, you can be experiencing extreme heat and still have to wait your turn to use the bathroom because it is not meant for you alone,” Baraka said.

Fueled by the accelerating effects of global warming, Sokoto has emerged as a focal point of climate vulnerability, enduring prolonged stretches of extreme heat that now persist for nearly half the year.

Also, in parts of northern Nigeria, residents face up to 150 days of annual extreme heat stress, a trend that is placing a severe strain on public health, traditional agriculture, and economic productivity. Findings from researchers reveal a critical need for targeted interventions to protect the region’s most-vulnerable populations from the deepening risks of long-term heat exposure.

“A more conducive place to stay will help us fight the heat because we are really crowded here and have no privacy at all. Whenever people are passing by, they can see us. We want a kind of place where we will have better ventilation and privacy to be able to dress lightly when it is very hot,” Baraka also said.

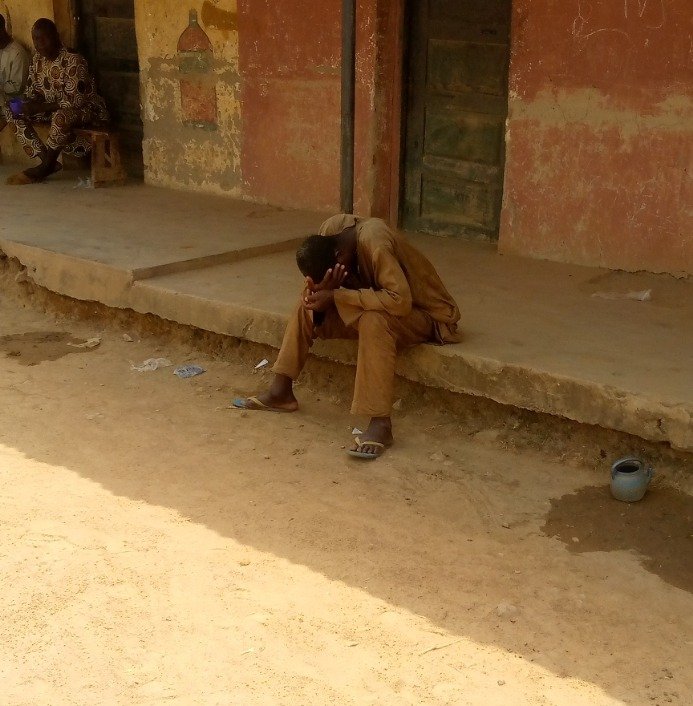

An assessment of five informal displacement camps in Sabon Birni by EcoPivot confirms the harrowing accounts of dozens of women.

The camps are severely overcrowded. Families live in confined spaces where distress is visible. In nearly-airless rooms, women and children sweat profusely, showing clear signs of physical exhaustion. For many, the afternoons and nights are spent in a heavy, distressed silence, punctuated only by occasional cries of children enduring the stifling conditions.

Dozens of mothers and pregnant women interviewed described the environment as increasingly unbearable. They said the combination of overcrowding and record-high temperatures has made the camps unconducive for maternal and infant health.

“We feel the heat more as women because we cannot take off our clothing in public unlike a man who can comfortably take off his cloths with no issue. Living here can never be like home, we just have no choice than to cope with the situation,” Basira Salihu, 29, a mother of three children said.

“A better place for us to stay is very important to curb the effect of the heat. The heat is worse with over 50 people sharing a small classroom. Sometimes the heat can be so intense, I can hardly breathe,” Aisha Salisu, 24, said.

Exposure to extreme heat is increasingly linked to a spectrum of severe health risks, ranging from cardiovascular and respiratory distress to kidney disease and mental health challenges.

Beyond these immediate threats, a growing body of scientific evidence is sounding a “consistent and concerning signal” regarding the impact of rising temperatures on maternal and fetal health.

“The heat is harsh and uncomfortably. It severely affects me and my unborn baby. I can tell how uncomfortable my baby is by the frequent unusual kicks which also affects me. I don’t feel relaxed due to the pregnancy and the heat makes it worse,” Umma Murtala, 27, said.

“We really do not have a choice other than to manage the situation. Some of the things we do to feel better is by taking regular shower and take a stroll outside a cooler place or sit under a shade. We also use the locally made hand fan to blow air on ourselves. All these don’t really help, especially during the peak of the heat,” Rakiya Muhammed, 35, said.

According to the National Library of Medicine, epidemiological studies indicate that exposure to extreme heat is closely associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, including stillbirth and low birth weight.

The timing of heat exposure is critical to fetal development. Research suggests that extreme heat during the first trimester may contribute to congenital heart and neural tube defects. Exposure during the later stages of pregnancy can trigger premature birth and impede fetal growth.

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) notes that pregnant individuals are significantly more vulnerable to heat exhaustion and heatstroke than the general population. This heightened risk is rooted in the immense physiological demands of pregnancy because the body must work twice as hard to regulate core temperatures for both parent and child. Dehydration heightens the risk, crippling the body’s natural cooling mechanisms and threatening an already fragile physiological balance. When perspiration fails, the body loses its primary defense against rising internal temperatures, turning a hot day into a life-threatening medical emergency for expectant mothers.

“Extreme heat is a serious threat because the body is already working overtime,” said Dr. Wodudat Muhammed, a physician based in Nigeria who spoke to The Liberalist. Dr. Wodudat explained that because a pregnant woman’s body works harder to support a developing baby, it struggles to cool itself down efficiently.

In environments such as displacement camps, where residents often lack adequate shelter, the risks are compounded. “If a pregnant woman is exposed to heat for too long, her core temperature can climb to dangerous levels, putting both her and the unborn baby at significant risk,” the medical doctor said.

While maintaining hydration is a critical defense, Dr. Wodudat emphasised that the challenge goes beyond water intake and bathing.

“A lot needs to be done here. Moving these families into well-built, climate-resilient homes is absolutely essential. Overcrowding in rooms must be looked into so as to bring down those indoor temperatures. How about small battery-supported fans? More trees should be planted across the area to create natural shade,” climate expert Barakat Momoh told The Liberalist.