OKUTA, Nigeria — Before sunrise, Aisha Abubakar used to leave her home in this border town in north-central Nigeria with an empty sack and a sense of certainty. Shea season meant income. It meant school fees would be paid, medical bills settled, and that, for a few months during the rainy season each year, women like her would earn money of their own.

Today, the situation has changed.

Across Nigeria’s shea-producing belt, a government ban on shea nut exports has driven prices down, disrupted long-established trade, and left women collectors and small traders absorbing the losses. Interviews with stakeholders confirmed that a policy meant to support domestic processing has instead squeezed rural livelihoods at the base of the supply chain.

“The season was everything for us,” said Aisha, a mother of five and wife to a farmer in Okuta, Baruten Local Government Area of Kwara state. “If you woke up early and worked hard, you knew what you would earn. Now, it’s no longer the case.”

The Genesis

Nigeria is the world’s largest and leading producer of shea nuts, accounting for an estimated 500,000 tonnes annually, or roughly 40 percent of global supply. Yet despite this scale, the country captures less than 1 percent of the global shea products market, which is valued in the billions of dollars and dominated by processed butter used in cosmetics and food industries.

Because of the country’s inability to produce more of the finished shea products as it does with the raw materials, in August last year, the government imposed a six-month ban on the export of raw shea nuts, arguing that the restriction would encourage local processing and reduce dependence on exporting unprocessed commodities. Officials said the policy could help grow industry earnings from $65 million to $300 million a year, if domestic value addition expanded.

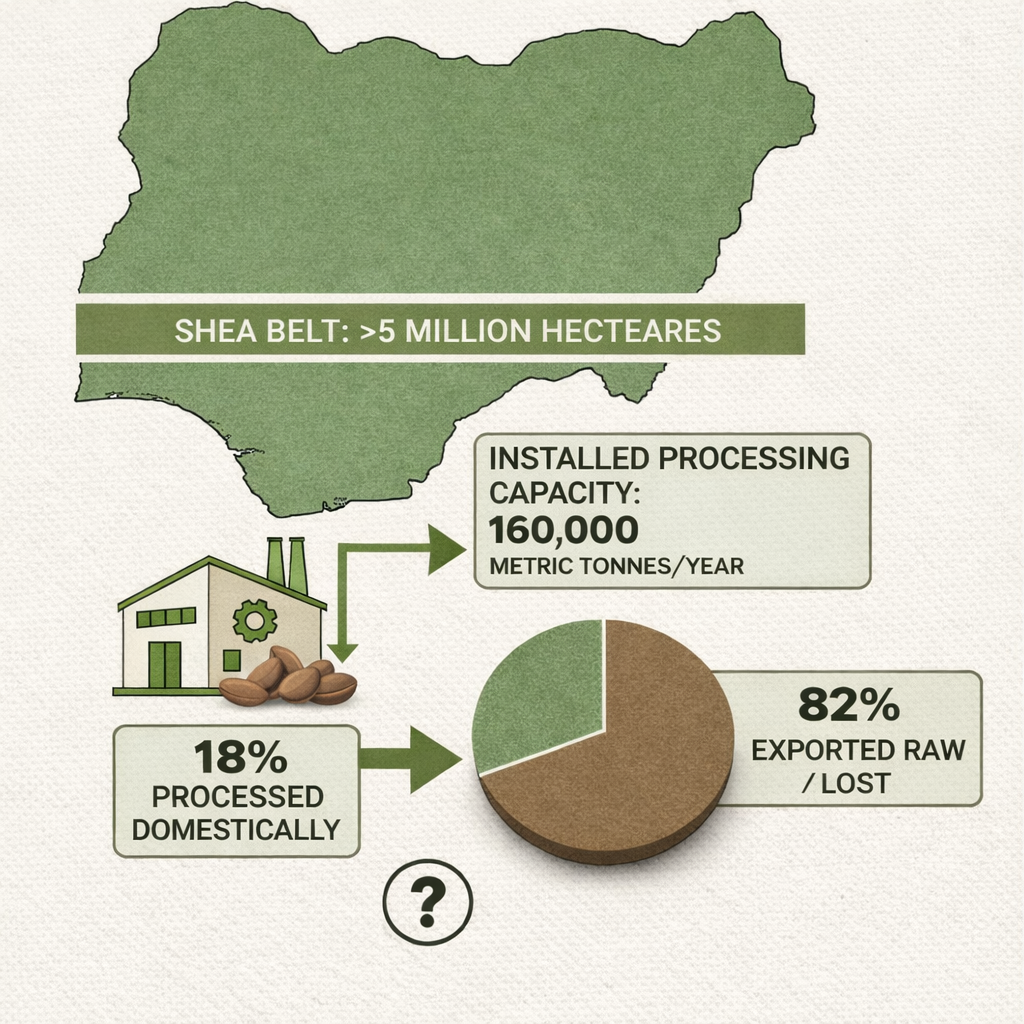

Though the ban is intended to secure raw materials for domestic processors, industry analysts say Nigeria’s current processing capacity is far too limited to absorb the sudden surplus created by the policy. According to Agusto & Co.’s Market Intelligence (AMI), a research platform that provides industry analysis across sub-Saharan Africa, existing shea processing facilities in Nigeria are operating at only 35 to 50 percent of installed capacity, leaving large volumes of shea nuts stranded in producing communities once export channels were cut off.

Nigeria’s shea belt spans more than five million hectares of wild shea trees, with total installed processing capacity estimated at about 160,000 tonnes per year. Yet only a small share of this potential is being utilised. AMI estimates that just 18 percent of harvested shea nuts are processed domestically, while the bulk is either exported raw or lost through informal cross-border trade. This structural gap means domestic processors were never positioned to take in the sudden influx of supply triggered by the export restriction.

The mismatch between supply and processing capacity quickly showed up in prices. According to Bloomberg, traders recorded a price plunge of about 33 percent in the weeks following the ban, with shea nut prices falling from roughly ₦1.2 million to ₦800,000 per tonne.

Interviews with women collectors and traders across Kwara, Oyo, and Niger states show the policy has depressed farm-gate prices, reduced buyer activity and forced thousands of women who dominate shea collection to store unsold stock or sell at a loss.

A Seasonal Economy Built by Women

Shea collection in northern Nigeria is overwhelmingly women’s work. Government and industry estimates suggest more than 90 percent of shea pickers and primary processors are women, most of them in rural communities with limited alternative income.

During the harvest season, married women in farming households gather nuts at dawn before turning to domestic labour later in the day. For many, it is their only independent source of income. One of them is Aisha. She has been collecting shea nuts since childhood. In strong seasons, she earned more than ₦200,000, a significant sum in rural Kwara.

Though prices have always fluctuated, recent years brought unusually strong returns. In 2023, shea nuts sold for about ₦25,000 per basin in Okuta. In 2024, prices doubled to around ₦50,000 naira in some markets.

By August this year, after the export ban made headlines, prices fell drastically with buyers offering about ₦18,000 per basin, a drop of more than 60 percent from last year’s peak.

“I don’t know whether to sell or keep it,” said Aisha. “If I sell now, I lose.”

She currently has four 100-kilogram sacks stored at home, waiting for prices to recover.

Buyers Pull Back

For decades, shea nuts from Okuta moved south through Yoruba traders from southwestern part of the country or across borders to the neighbouring Benin Republic. Since August last year, cross-border buyers have disappeared.

“Only the Yoruba buyers still come,” Abubakar said. “And even them, not like before. When they came we just saw they started pricing the shea lower than before.”

In Nigeria’s shea economy, women like Aisha rarely sell directly to processing companies. Instead, their harvest passes through a network of mostly male traders and aggregators who buy from village collectors, bulk the nuts, handle drying and storage, and transport them to urban processors or export markets. When these middlemen pull back, the impact is felt first — and most sharply — by the women at the bottom of the chain.

One of the middlemen in Saki, Oyo state, is Mufeed Alade, a shea aggregator. He said his business collapsed after the price fell. He bought nuts from Mokwa and Bida in Niger state, dried and sorted them, and sold them in bulk to processing companies in Ibadan and Lagos. He did not export directly, but his business depended on the steady movement of shea from women in the villages to factories.

“I bought at high prices and stored,” he said. “By the time I wanted to sell and restock, the price had already gone down.”

After holding the goods for many weeks, he said he later sold at loss and exited the business.

Another middleman is Isma’il Biliaminu, an Okuta-based farmer and a recent public administration graduate from Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto. Growing up in Kwara state, he learned early how profitable the shea nut trade could be.

Biliaminu said he used savings from his national service year to enter the market in June last year, buying shea nuts at ₦20,000 per basin with the plan to use the proceeds to kickstart a master’s degree.

Then the export ban took effect.

“Now they are selling at 18,000 naira,” Biliaminu said. “And the buyers are no longer coming.”

He is holding two and a half 100-kilogram sacks. Each week he waits carries the risk of further price drops or spoilage.

“It is a risk,” he said. “But selling now means loss.”

The core problem, Biliaminu says, is not production but demand. “I have done my research, and my findings revealed that there are not many companies in Nigeria that process shea, but there are too much supply,” he said.

Biliaminu sits in the middle of the shea economy; one of the small traders who buy directly from village women and move their produce onward to larger buyers, linking rural collectors to national and international markets. And since the export ban, many traders like him have stopped buying, leaving the women collectors with few buyers.

Too Much Supply, Too Little Capacity

The shea economy disruption comes as Nigeria pushes to diversify away from oil exports. Official trade data show that non-oil exports rose by about 19.6 percent in the first half of 2025 to $3.2 billion, driven largely by established commodities such as cocoa and fertiliser. Policymakers framed the shea export ban as part of this same diversification strategy, an effort to move Nigeria up the value chain by processing raw materials domestically.

But unlike cocoa or fertiliser, shea lacks the scale of domestic industrial capacity needed to absorb sudden policy shifts. While larger non-oil commodities benefit from mature processing ecosystems and export infrastructure, Shea remains heavily dependent on informal trade networks and small-scale buyers. Cutting off export channels without first expanding processing capacity has shifted the costs of adjustment onto women collectors and small traders least able to bear them.

Since the ban took effect, exports of raw shea nuts have slowed dramatically, according to traders and industry participants, cutting off a key foreign-exchange channel for producing regions. Over time, the export slowdown risks shrinking Nigeria’s share of global shea supply as international buyers turn to alternative sources. Suppliers fear if the policy persists for a long time, it will weaken or even deter future export earnings even if the ban is lifted.

But the export ban did not emerge in a vacuum. It followed the launch of what Nigerian officials have described as a landmark investment in domestic shea processing, a move that could have influenced trade policy to the path of restriction.

Last year in Niger state, one of Nigeria’s main shea-producing regions, Salid Agriculture Nigeria Limited inaugurated what it called Africa’s largest shea butter processing facility, with an installed capacity of about 30,000 tonnes per year. The plant, located in Mokwa Local Government Area, was presented by federal and state officials as evidence that Nigeria was finally ready to move up the shea value chain.

Government officials framed the export ban as a way to secure raw materials for such facilities, ensuring that nuts were processed locally rather than shipped abroad in raw form. But industry analysts and traders say the leap from factory launch to export ban ignored a basic arithmetic problem.

Nigeria produces an estimated 350,000 to 500,000 tonnes of shea nuts annually. Even at full capacity, the new facility — Africa’s largest — can absorb less than 10 percent of national output.

Because of the deficit in the local production and processing, Mohammad Jagaba, a shea processor at Jummy Factory in Niger state, said the ban abruptly reversed long-standing market dynamics built around seasonal exports.

“When the order comes from outside Nigeria, that is when the business really works,” Jagaba said. “You don’t sell at the same price you sell inside the country. You sell at least two or three times higher.”

Before the restriction, Jagaba said exporters and large domestic buyers regularly placed advance orders, allowing traders to plan purchases from villages and stock warehouses ahead of peak demand. That demand has since disappeared.

Jagaba said foreign buyers began pulling back within weeks of the ban, initially waiting to see whether the policy would be reversed before cancelling orders altogether. By about a month in, many had stopped buying entirely, forcing traders holding large inventories to sell domestically at a loss.

“If you have hundreds of tonnes in your warehouse and the government says they don’t want people to come from outside to buy again, you must bring down the price,” he said. “Otherwise you lose everything.”

Prices that once bottomed out around ₦60,000 per bag before the ban, Jagaba said, now trade for ₦20,000 to ₦25,000, as sellers rush to liquidate stock they can no longer export. The collapse has rippled through a supply chain dominated by informal actors.

The price crash has been felt most acutely by rural women at the base of the chain. Jagaba described the situation of these women collectors as people who now store unsold nuts at home, wait for buyers who may not come, and later sell at reduced prices to meet urgent household needs.

“If there is no food in the house, you must sell,” he said. “Even if the price is bad, you have to feed your family.”

Unlike the women at the bottom of the chain, who have very limited options, some processors have tried to adapt by increasing the production and sale of shea butter, which remains legal to export. But Jagaba said this shift has not been enough to make up for the losses caused by the collapse of the raw nut trade.

With demand weakened and orders reduced, the pace of work has slowed. Though “there is still work, it is not like before,” Jagaba said. “Before now, I would be busy from morning till night. Now sometimes you just sit and talk.”

What the Ban Gets Wrong — Expert

Dr Farouk Bibi-Farouk, an economist and lecturer of Political Economy at the University of Abuja, says Nigeria’s decision to curb raw shea nut exports is not inherently misguided. In theory, he adds, the country is right to try to move up the value which is an intuition of a government who wants development for the country.

The only problem, he argues, is that markets do not work on such intuition.

According to him, if Nigeria fully refined its shea nut and exported shea butter and its derivatives, industry earnings would rise significantly. Shea by-products, he added, are used far beyond cosmetics and food, extending into pharmaceuticals, fashion, and even advanced industrial applications.

But Dr Bibi-Farouk insists that value addition cannot be forced by restriction.

“There was no need to ban exports,” he said. “If you create strong local demand, good profit margins, and the right incentives, the market will naturally absorb the raw material locally. Nothing will be left to export.”

Instead, he said, the government reversed the sequence by restricting exports before building the industrial capacity and market infrastructure needed to replace them.

The result, explains Dr Bibi-Farouk, was predictable. Once exporters were cut off and domestic processors proved unable to absorb the surplus, demand collapsed and prices crashed, leaving the people at the bottom of the value chain with little or nothing to profit.

‘We Are Husband-Dependent Again’

Safiyat Jibril is a shea nut collector and mother of two in Okuta. Shea season once marked the most economically meaningful months of her year. With her husband focused on farming, the nut was her own source of income, money she earned independently and used to support her household expenses.

“Once the season started, I woke up very early every day. If you delayed, you would lose out because many people were also searching for them,” she said.

The work was demanding. The women endure long hours under the sun and battle competition across villages. But the reward, she says, justified the effort. The more nuts Safiyat gathered, the more she earned. And crucially, she knew there would be buyers.

Safiyat has been collecting shea since before marriage, as early as when she was a young girl in her parents’ home. Over the years, it became a reliable pillar of her household income. In good seasons, she earned more than ₦250,000, a sum that helped buy food, clothe her children, and cover parts of their school expenses.

When the price of shea nut per basin fell to ₦18,000 in August, she hoped it was not real.

Safiyat recalls her last few sales clearly. In July, she sold two basins to a Yoruba trader from outside the town and earned about ₦50,000. In August, she managed to sell one basin for ₦25,000. Since then, she has refused to sell again.

Today, four sacks of unsold shea, each weighing about 100 kilograms, sit in her storage. But holding on is a gamble. If she sells now, she loses money. If she waits too long, quality may decline and buyers may use that as leverage to offer even less.

“The price keeps falling,” she said. “I don’t even know whether it will rise again.”

Safiyat said she had no idea an export ban was in place when buyers began offering what she considered ridiculous lower prices for shea nuts. By the time word filtered into the community, the damage had already been done, with the regular traders from Benin Republic no longer showing up and Nigerian buyers reducing their visits.

The impact has since rippled through daily life in ways that go far beyond the market. Safiyat’s contribution to household budgets fell off and over to her husband.

What the ban has taken from her and other women in Okuta, she explained, is not only income but independence. Shea money was the one source of cash they controlled themselves, money that allowed them to contribute to their household.

“The hardest moment was when I needed money urgently and realised that even if I sold my shea, it wouldn’t be enough,” said Safiyat. “Shea was our own money. Money we didn’t have to beg our husbands for. Now, we are husband-dependent again.”

The Liberalist forwarded our findings to the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security asking whether the policy outcomes were anticipated and if the ministry would support an extension or suspension of the policy. No response has been received as of the time of filing this report.

What women in Okuta are experiencing is not just a loss of income, says Alu Mary Ojima, a gender and social inclusion expert with the Girls and Goals Initiative, but also a shift in power within the household. She said Women’s access to independent income is directly linked to their bargaining power within households.

Ojima added that such outcomes are consistent with what gender-economics research has long shown. When women’s income declines, their ability to influence household decisions and priorities decline as well.

According to her, what is happening in Okuta reflects an oversight in the policy process. Because the regulators focus narrowly on value addition targets, the government failed to account for how sudden market disruptions would affect women who depend on shea for financial independence.

“Gender impacts do not appear to have been adequately considered in the design or implementation of this policy. This is not just an industrial policy issue. It is a question of whether economic reforms will expand women’s livelihoods or quietly erase them in the name of value addition,” she said.

Ojima’s argument draws weight from Nigeria’s own policy commitments which the export ban seems to contradict. The National Gender Policy (2021-2026) provides a clear framework for ensuring that women have equal access to income-generating opportunities and the ability to control and manage their earnings, particularly in rural communities. Section 3 of the policy emphasises that women must be able to participate fully in agriculture and trade while maintaining financial independence within their households. The policy further reinforces this by requiring that all government programs and policies integrate gender considerations throughout planning, implementation, and monitoring, and in sectors where women predominate, the government must conduct a gender impact assessment.

Efforts to obtain a comment on these concerns from the Federal Ministry of Women Affairs were unsuccessful. Messages seeking clarification on whether gender impact assessments were conducted before the ban and how to safeguard women’s livelihoods if the policy is extended were sent to the Ministry. But as of the time of publication, no response has been received.

_____________

Edited by Ibrahim Adeyemi