Barely a week after Guinea-Bissau’s military overthrew its democratic government, the Armed Forces in Benin attempted to depose President Patrice Talon, who had been in office since 2016. On Sunday morning, soldiers proclaimed that they had toppled the government. But Alassane Seidou, Benin’s minister of interior and public security, later clarified that the coup was simply an attempt and had been foiled.

President Talon’s attempted ouster indicates deteriorating insecurity in the country’s northern region. Now marked as the twelfth junta-led power seizure since 2020, political leaders say these coups are direct consequences of failed democratic leadership across the West African region.

While President Talon’s one-decade tenure is expected to end by April 2026, the Constitutional Court recently confirmed an extension of the presidential term from five to seven years, with a two-term limit. Analysts say this decision favours the President’s Finance Minister and endorsed successor, Romuald Wadagni, and aims to cement President Talon’s influence in power for a long time.

Before the coup, the BTI Transformation Index, an analysis of transformation processes toward democracy, regarded Benin as one of the most stable democracies in West Africa. But over the decade, President Talon’s administration has faced accusations of criticism suppression and worsening insecurity.

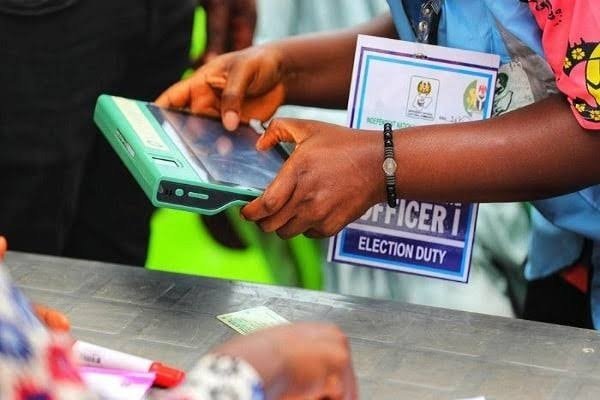

Two months ago, the National Autonomous Electoral Commission (CENA) banned Les Démocrates, Benin’s main opposition party, from the April 2026 Presidential race because the party did not meet the required 28 legislative sponsorships as requested under the new electoral code. CENA ruled out what would have counted as the 28th sponsorship as “invalid sponsorship,” reigniting political tensions already fuelled by the arbitrary detention of critics.

It was not the first time President Talon would rule out opposition through reforms. The same fate has marred previous elections.

Before the 2019 parliamentary elections, Talon reformed the electoral law to allow the Ministry of Interior to issue a “certificate of conformity” to vying political parties, a code Freedom House described as “restrictive” after the electoral body approved only “two pro-government parties” for the elections. The elections also saw a heavy crackdown on journalists and violence against demonstrators who challenged the zero-opposition election.

In 2021, Talon reformed the electoral code again. This time, political parties must get sponsorships from parliament members or mayors, a threshold opposition parties could not meet after the 2019 parliamentary sweep excluded them. In the same year, security forces arrested Reckya Madougou, an activist and former minister of justice who was also a renowned critic of Talon. She was later charged with terrorism charges, which the New York Centre for Foreign Policy Affairs say is politically motivated. Reckya has been in detention ever since.

These repressive approaches, coupled with the continued deterioration of the security situation in Northern Benin, prompted the coup, the arrested soldiers declared in a statement. The coup plotters also pointed out a decline in healthcare benefits amidst rising taxation and curbs on opposition activities.

But Benin is not the only country to experience a coup under such circumstances. In fact, findings show that most African countries where coups have resurfaced experienced either political repression or chronic insecurity issues.

Guinea-Bissau’s Coup

Just like Benin, political repression clouded the series of events that led to the military takeover in Guinea-Bissau. Since President Umaro Embaló’s power takeover on February 20, 2020, the press has recorded more than three incidents of violent raids by masked men and the military.

Guinea-Bissau’s latest coup is the fourth successful one among 10 attempts since it gained independence from Portugal in 1974. General Horta N’Tam, Guinea-Bissau’s transitional president, says the takeover was necessary and urgent because “the country is in a politically difficult and delicate phase.”

After Guinea-Bissau’s successful coup, the Economic Community of West African States responded with an immediate suspension, describing the takeovers as unconstitutional and unacceptable. As the country joined the list of suspended junta-led West African states, Timi Frank, a Nigerian politician and diplomat, described it as a symptom of deepening governance failures across the continent.

“How can AU and ECOWAS condemn coups with moral authority when they look away as leaders rig elections, intimidate opponents and extend term limits illegally?” Queried Timi.

“Rigged elections, constitutional manipulation, suppression of opposition and leaders’ refusal to give up power are political coups that embolden soldiers to intervene,” Timi warned.

Away from Guinea-Bissau and Benin, coups and demonstrations are fast becoming a common reaction to poor leadership across Africa. In late September, President Bola Tinubu ordered a significant shake-up in Nigeria’s military after Major General Emmanuel allegedly uncovered a coup. The past two years of President Tinubu’s administration have witnessed a series of protests and demonstrations against bad governance and economic hardship, the majority of which security forces violently repelled.

“West African countries have been pretending to practice democracy, but leaders use the system as a platform to sustain themselves in power,” Adama Gaye, ECOWAS’s ex-director of communications, decried. But it is not just a West African problem.

A few days into October in East Africa, Madagascar’s military ousted its democratic government and announced a junta-led rule. The army takeover followed youth-led street demonstrations against poor leadership and corruption that almost escalated into a civil war, just before the military takeover. After the coup, citizens filled the streets in jubilation, a scene similar to that seen after the military takeovers in Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso.

Also, this year, Tanzania experienced post‑election protests against the backdrop of bad governance, rigged elections and opposition suppression, with security forces responding with a widespread clampdown.

After the October 29 election that confirmed former President Solulu Hassan’s re-election with a 98 percent landslide win, protests erupted from the polls, contesting the banishment of rivals amidst political repression.

Before the election, President Suluhu’s government had arrested and charged Tanzania’s main opposition leader Tundu Lissu with treason for holding a rally advocating constitutional reforms. He was detained at a maximum security prison. The country’s electoral body also banned Luhaga Mpina, Tanzania’s second biggest rival after Tundu, from vying, leaving Suluhu with unpopular candidates from smaller political parties.

At the polls, the East African nation experienced a nationwide digital blackout amid a heavy crackdown on demonstrators.

“Hundreds of protesters and others were killed, and an unknown number injured or detained for demonstrating against the disputed election,” reports from the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights revealed.

A CNN’s investigation reveals how morgues were overflowing with corpses, with security forces seen removing bodies from streets and hospitals and disposing of them at undisclosed locations. At the same time, some were buried in a mass grave at the Kondo cemetery in Kunduchi, north of the city.

If political repression persists, Timi says the military will continue to intervene.

“Until leaders become very serious and honest about promoting real democracy, which covers the rule of law, good governance, and freedom of expression, military coups will continue to be a reality in West Africa,” Gaye warned.