OSHODI, LAGOS. Anisere Sodiq knew about online doctors attending to patients virtually. But he did not believe in its effectiveness until he had a severe ulcer-triggered stomach ache and needed instant cost-effective care.

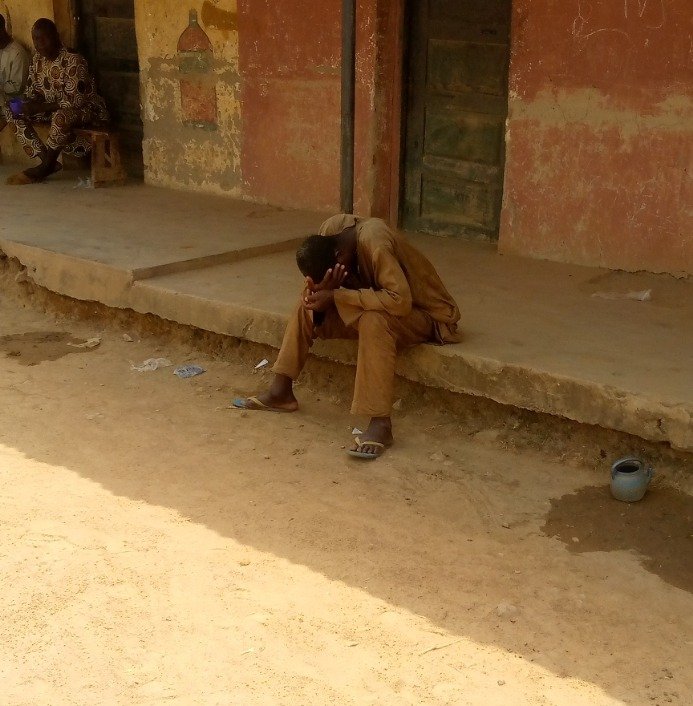

Sodiq, 34, runs a small barber shop in Oshodi, Lagos State, barely making enough money for his feeding. When the stomach upset started one day in April this year, he could not afford the cost of checking in with a doctor at a physical healthcare facility.

Before then, a friend had told him about iWello, a website where patients could talk to a medical doctor and get help. So within seconds, he opened the web page on his phone and read through the process of speaking to a doctor.

“I had no other option,” he said. After creating an account, he saw a lineup of about seven doctors available online. He glanced at a banner reading “Doctor Ruth” with details about her qualifications and experiences.

When he clicked on the banner, a paywall page appeared requesting the payment of N300 ($0.72) to proceed. A moment after he paid the amount using his debit card, he was chatting with Doctor Ruth, and a medical consultation began.

After explaining his condition, the doctor recommended some tests, including abdominal scans, to determine the status of his stomach. He quickly ran the tests at a recommended lab close to his location, and when the results came out the next day, he snapped and sent them to the doctor.

“The doctor told me I was lucky,” he said, implying that his stomach aches could have developed into some more serious condition had he not acted quickly. “She prescribed some drugs for me, and I became okay in a couple of days.”

iWello is one of several startups in Nigeria using remote communication to provide medical consultation, diagnosis, and treatment. This approach falls within a globally growing field called telemedicine, which involves using digital devices like computers and smartphones to provide healthcare services remotely.

The average cost of out-of-pocket consultation at a private health centre in Nigeria is N10,890 ($26). And that is high in a country where 83 million or 39 percent of the population live in extreme poverty. But for Sodiq, paying as little as N300 (less than a dollar) for a consultation to get instant help was like bringing a hospital to his home at an insignificant cost.

Underfunding

At the “Abuja Declaration” in 2001, African leaders pledged to allocate 15 percent of their countries’ budgets to the health sector annually, but only Rwanda and South Africa have met the target.

Since 2001, Nigeria’s annual health sector allocation has not gone beyond 7 percent, the highest being 6.2 percent in 2012. The underfunding has left most public secondary health centres and two-third of the 30,000 public primary health centres in the country inadequately furnished, under-staffed, and sometimes not functional, resulting in 70.5 percent of Nigerians paying for healthcare out-of-pocket.

Adeyinka Shittu, a health policy researcher at the Private Sector Health Alliance of Nigeria, said that telemedicine outlets are filling the gaps left by private and public health sectors in some way.

“If we look at it, these [public] primary health centres are meant for the low and middle-income people. But it is not receiving much attention from the government. So this [telemedicine] innovation could serve the poor [if given the needed attention],” he said.

Ismail Adejonwon, iWello’s founder, grew up in the low-income suburb of Oshodi, Lagos State. When he was 14, his mother regularly suffered stomach upsets from appendicitis. During one of such upsets, her condition worsened because the family could not get her immediate treatment for lack of funds.

“The doctor said she would need a minor surgery because we had delayed it [for days]. My father was a civil servant who expended his salary on family needs, and my mother was a petty trader. We struggled to get the money to pay for the surgery,” he said.

His mother became well after the surgery. But later, he started thinking that if the family had access to low-cost instant help, his mother probably would not have suffered for long. This inspired Adejonwon, a digital marketing consultant, to start iWello in June 2021.

‘Not for the money’

Telemedicine advocates say it saves cost, reduces the stress and time of visiting a hospital frequently, and eases the management of life-threatening diseases like diabetes and hypertension.

iWello’s 29 doctors work part-time, and at least seven are available online per time. An iWello-doctor agreement allows a doctor to take 70 percent of every N300 consultation fee paid, while iWello, which won a $750 pitch competition last year, takes 30 percent.

iWello started exactly one year ago, and patronage is still very low – just 500 subscriptions and a little above 100 consultations since launch. That suggests a shaky future because the low patronage means, on average, a doctor takes home something as little as N1050 weekly per the 70 percent cut.

But the doctors say they offer their part-time service, not for the money but to help patients who need care the most access it at near-zero cost.

“iWello is aimed at providing affordable healthcare to low-income earners, and as a doctor that has this same goal…my dreams are being achieved,” said Fatima Karem-Ajayi, one of iWello’s general medical practitioners.

Nonetheless, Adejonwon, iWello’s founder, said iWello is planning to raise resources through crowdfunding and grants to pay its doctors better and expand its service beyond mere consultations.

mDoc, another telemedicine startup in Nigeria, charges N500 ($1.5) per consultation. And through its “Propel Programme”, mDoc provides free access to private health coaching groups and virtual exercise classes to its paying subscribers.

Hauwa Omeiza, 37, one of the participants of the Propel Program, said she joined to keep her blood pressure in check and reduce her weight, which was 91.4 kg a few months ago.

“I set a goal to achieve a target weight of 80 kilograms (kg) and maintain a stable blood pressure of 138 millimetres of mercury (mmHg). Eighteen weeks into my journey, I have lost 7.4 kg bringing my new weight to 84 kg, and I have maintained a stable blood pressure below 138 mmHg,” Omeiza said.

She said through the programme, she learned to incorporate more fruits and vegetables into her food and became more intentional about her exercise to achieve the target. mDoc has 72,000 members on its digital health platform.

Health Connect, another telemedicine startup, offers unlimited access to doctors via voice and video calls at a N1,000 ($2.4) monthly subscription or N6,000 ($14.5) annually.

More limitations

Opponents of telemedicine say it makes people who patronise it believe it is a substitute for visiting a health centre. But Adejonwon said iWello’s doctors try to safeguard against it by telling patients up front that its service is not a substitute and by referring patients to physical health centres if the condition demands it.

Also, the use of telemedicine requires a technology-friendly environment to thrive. About 81 percent of Nigerians lack meaningful connectivity (a combination of a 4G connection, owning a smartphone and daily use of an unlimited broadband connection) at home.

“Nigeria does not have adequate facilities ready [like ICT infrastructures in rural areas], especially for the low-income households, which makes it difficult to reach those who need telemedicine the most,” said Shittu, the health policy research expert. “[Even] to say that telemedicine will make healthcare accessible to the poor is perverted when the internet cost is high in the country.”

He proposed that “we could find low-cost high volume alternatives. Rather than operating a web page, which the poor and illiterate might find difficult to access, we can start having call centres where people could go and consult a doctor via a phone call.”

And telemedicine needs to be integrated into Nigeria’s national health system to sustain it, Shittu said. He called for a new national policy to make the integration possible.

“If you have a web page that treats people for malaria but not adequately reflected in Nigeria’s data for malaria, the information won’t be available for people who need them to shape policies,” he argued.

___________

This story was produced with the support of Nigeria Health Watch through the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organisation dedicated to rigorous and compelling reporting about responses to social problems.