Despite billions of naira allocated for healthcare in Sokoto state, rural communities in the state are battling a silent but deadly crisis: collapsing health facilities, critical shortages of staff and medical supplies, and widespread neglect. As patients are forced to lie on bare floors without treatment, the reality on the ground sharply contrasts with the government’s promises of massive healthcare investments. In this investigation, SHEREEFDEEN AHMAD exposes the systemic failures crippling Sokoto’s healthcare system, revealing the human cost of broken policies, mismanaged funds, and abandoned rural communities.

This is the first in a two-part series uncovering the collapse of Sokoto State’s healthcare system, despite multi-billion naira allocations. You can read the second part here.

_______________

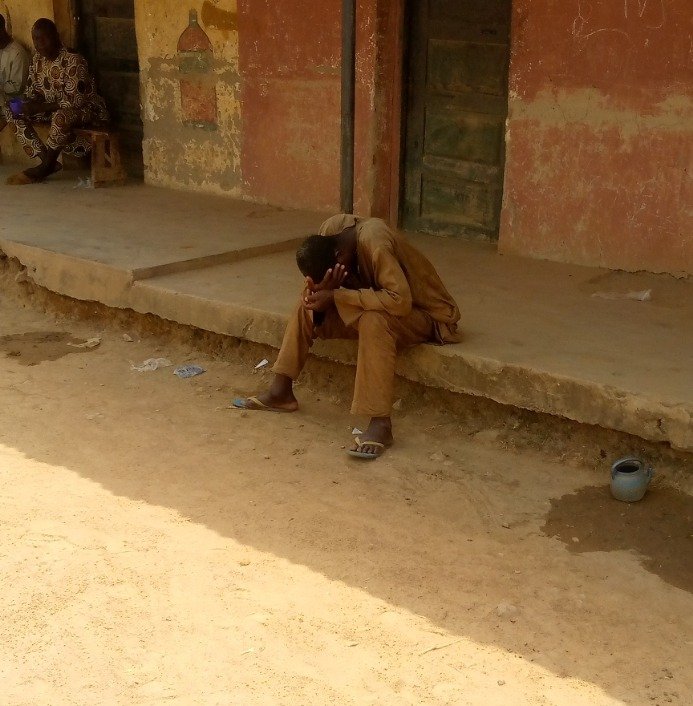

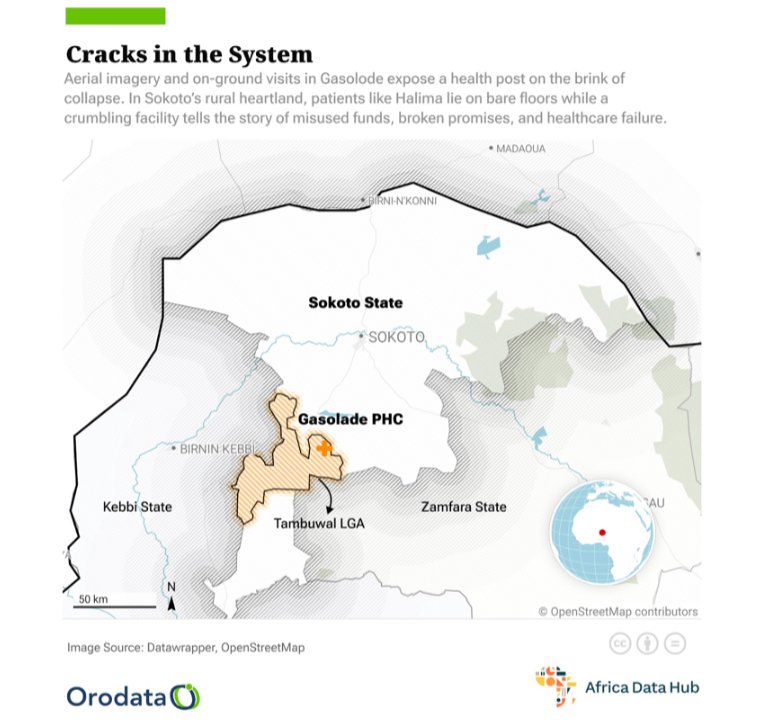

In December last year, 27-year-old Halima Muhammad battled a painful, unknown ailment in Gasolode, a remote village in Jabo ward of Tambuwal Local Government Area, Sokoto state, Northwestern Nigeria.

Her first hope for recovery rested on receiving sound medical attention at the government-run Gasolode Health Post. But upon arrival, a different reality embraced her. There was no place for her to comfortably lie, only the cold, dusty and bare floor. Weak and worsening by the minute, Halima collapsed onto the ground.

Writhing in pain, she waited for help. Eventually, a lone staff member appeared. Relief breathed over Halima, thinking her suffering was finally over. But little did she know it was only the beginning of her ordeal.

“The staff said there were no drugs to treat my condition,” Halima recalled, shaking her head as if reliving the agony. “I didn’t even know what was wrong with me. My whole body was in pain.”

With no treatment available and no proper place to rest, Halima continued to struggle on the floor as her condition worsened. Hours later, her brother managed to find a motorcycle to transport her to the Jabo Healthcare Center, about 25 kilometers away, where she finally received medical care.

Halima’s experience mirrors the daily plight of countless residents who rely on the Gasolode Health Post for survival.

When this reporter visited the facility in March, the scene was devastating.

The facility, which is meant to serve as the first line of action for treatment, now stands broken and barely functional.

The ceilings are torn open, exposing sheets of rusting metal and rotten wooden beams. In several places, large cracks creep across the walls, suggesting the structure itself could collapse without warning. Inside, the facility resembles an abandoned storage room rather than a functioning medical facility. Patient records, loose syringes, and some essential drugs are scattered across rickety desks. At one corner, a makeshift hanging rack meant for medical files hangs in tatters. There is no place to comfortably lie, and patients like Halima, if they come at all, are left to sit or lie on bare surfaces.

Sunlight moves through the tiny broken windows, highlighting the decay rather than offering relief. Evidence of neglect is everywhere, yet this is the only near option for thousands in the surrounding communities.

Shuib Adamu, a resident of the community, pointed to the building. “As you can see,” he said, “the entire health facility needs renovation. There’s nothing here that shows any attention has been given to it. We just want the government to refurbish everything and help ease our suffering.”

The Disconnect Between Sokoto’s Health Spending and Reality

Across Sokoto State, remote communities are grappling with a silent crisis: poor access to healthcare services, abandoned facilities, and severe shortages of medical personnel and equipment. These longstanding issues have only worsened amid a decade of insecurity and government neglect.

In 2023, the Sokoto state government allocated N100 million for the capital needs of Primary Healthcare Centres (PHCs). Yet, not a single naira was spent. By the first quarter of 2024, of the N890 million earmarked for PHCs for the entire year, just N308 million was utilized.

In 2024, the government announced a N10 billion investment to renovate, refurbish, and equip 244 PHCs across the 23 local government areas. Of this, over N6 billion was dedicated to infrastructure improvements, including the installation of solar-powered lighting, repairs of ambulances, and procurement of a Toyota Hilux for monitoring and supervision.

Bashir Ahmad Abubakar, a budget analyst with the Ministry of Budget and Economic Development, reaffirmed the government’s plan during a Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) quarterly meeting organized by USAID State2State. “The renovation will gulp over N6 billion, which includes full installation of solar-powered lights in all the primary health centres,” he said.

But despite these ambitious allocations, the reality on ground tells a different story. Many health facilities, especially in remote and rural areas, remain in a state of ruin, far from any standard of quality healthcare delivery.

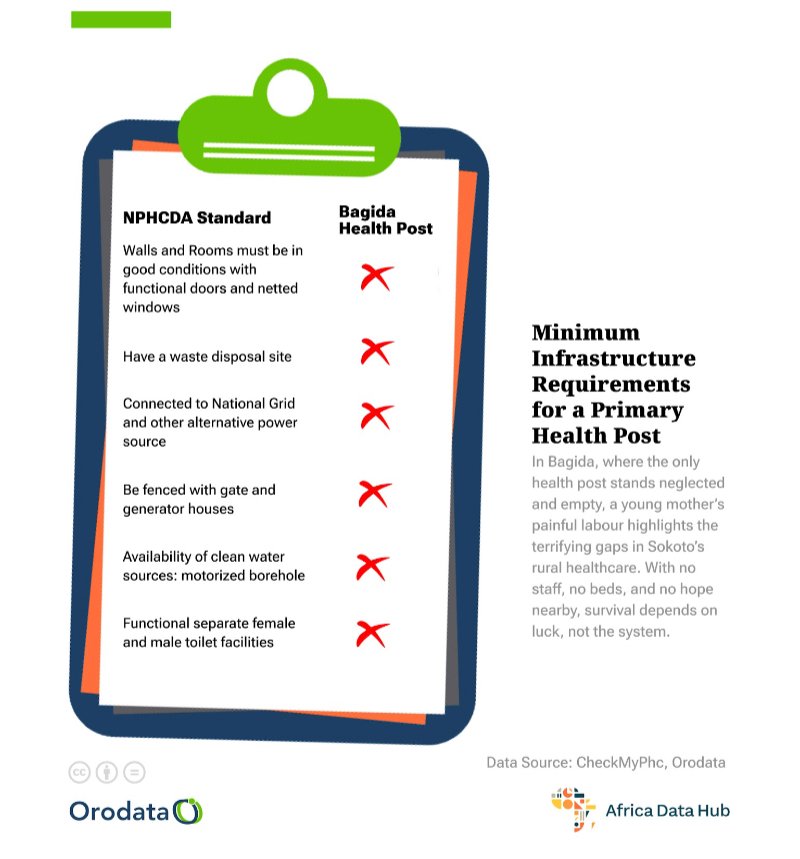

When The Liberalist visited Gasolode Health Post, Bagida Health Post in Tambuwal LGA, and Ruwa Wuri and Mogonho Health Posts in Tangaza LGA, we met them in shambles. These centres lack basic infrastructure, essential drugs, and qualified personnel, falling far short of the minimum standards set by the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA).

According to the NPHCDA’s “Minimum Standards for Primary Health Care in Nigeria,” a standard Health Post should have at least two rooms with cross ventilation, functional separate male and female toilet facilities with water supply, and a minimum land area of 1,200 square metres. The facility should be equipped with basic furniture and medical equipment necessary for providing essential health services.

In terms of human resources, a Health Post is expected to have a minimum of four staff members, including one Community Health Extension Worker (CHEW) and three Junior Community Health Extension Workers (JCHEWs). These personnel are responsible for delivering basic health services such as treatment of minor ailments, health education, referral services, and immunisation.

Health Posts are also expected to have basic medical equipment and essential drugs as outlined in the National Essential Drugs List to effectively provide preventive and basic curative care.

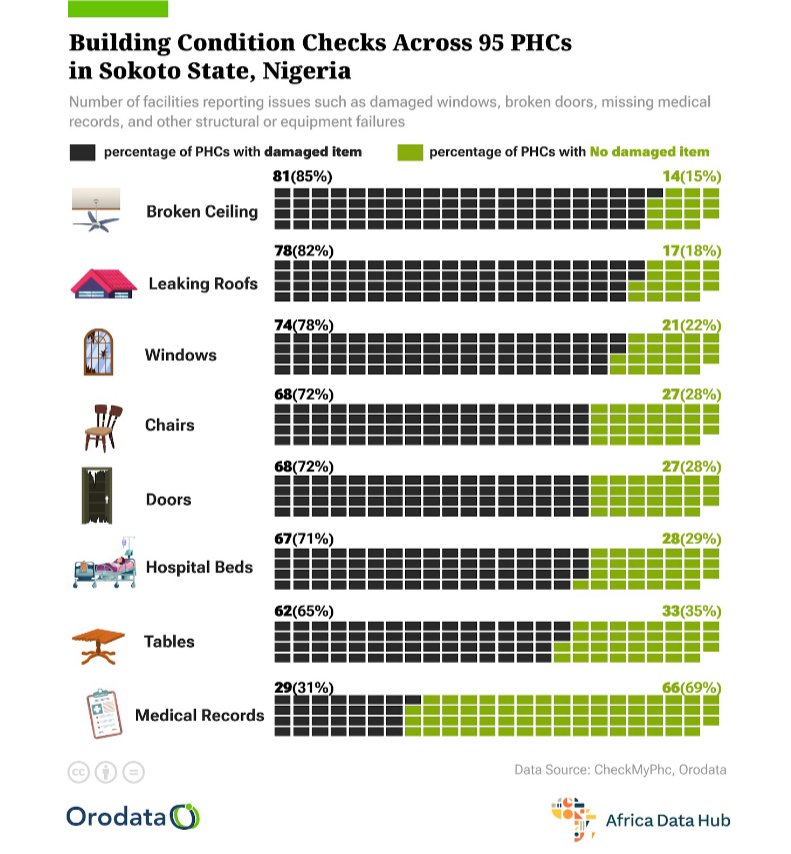

However, recent data from Orodata Science and Civic Tech, an organisation that uses data and research to improve institutional reforms in Nigeria, shows that 25 out 53 primary healthcare facilities surveyed in 2024 are in old and poor conditions. This highlights the fatal reality of the primary healthcare system in Sokoto state, which killed an estimated 1954 patients in the last one year, according to the report.

Meanwhile, Sokoto state is just a microcosm of the larger crisis. The situation is even more alarming at the national level: the World Health Organisation (WHO) reports that only 25 percent of Nigeria’s PHCs possess even a quarter of the minimum required equipment. Furthermore, only 20 percent are capable of providing basic emergency obstetric care.

“The Nigerian healthcare system is deteriorating, with PHCs showing significant infrastructural and operational weaknesses,” a 2024 MyPHC Report released by Orodata Science noted.

According to the report, half of the PHCs across the country suffer at least four major building failures. And 25 percent have not received recent upgrades, struggling with inadequate water, electricity, and sewage systems, while 28 percent lack access to clean water, relying on unsafe sources.

It also noted that there is a severe shortage of medical staff, with very few doctors or medical officers, pharmacy technicians, and health assistants.

“Although there are many Community Health Extension Workers (CHEWs), Community Health Officers (CHOs), and nurses, their numbers are still insufficient. Only 23% of PHCs report satisfaction with work conditions, and there is a 24% gap between deployed and active staff, contributing to poor care and low morale. Only 36% of patients find PHCs affordable. Overall, 49% of PHCs are rated as good and effective.”

The report calls on the government and health institutions to address the urgent need for improvements in PHC facilities. “This includes updating databases, enhancing staff welfare, training health workers, and effectively managing resources to ensure reliable healthcare services.”

Sokoto Among Nigeria’s Worst for Healthcare, Despite Billions Budgeted

In 2022, a report by The ONE Campaign, developed in collaboration with National Advocates for Health, Nigeria Health Watch, the Public & Private Development Centre (PPDC), and other partners ranked Sokoto among Nigeria’s 18 worst-performing states in Primary Health Care (PHC) service delivery.

The report, with a detailed and systematic assessment of the implementation of the Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF), state compliance with the National Health Act and National Health Policy, and overall health system performance, painted a troubling picture of healthcare delivery in the state.

This poor ranking came despite consistent multi-billion naira budget allocations to the health sector in Sokoto. Since 2020, the state has steadily increased its health sector budget. In 2020, for instance, it budgeted N21.9 billion for the health sector representing 11 percent of the total budget. In 2021, the sector got N17 billion—representing 17 percent of the total budget. In 2022, the health budget was put at N28.8 billion while in 2023, the health sector got N31 billion. The sector also received N30.42 billion in 2024.

Yet, the numbers tell only half the story. On the ground, little has changed, particularly in rural communities where healthcare access remains scarce, and PHCs are either non-functional or severely under-equipped.

The billions allocated on paper have yet to translate into tangible improvements for the people who rely on these facilities. For many residents, quality primary healthcare remains a distant dream, lost in the cycle of systemic neglect.

Lawal Jamiu, a northern-based public health analyst said one of the causes of the healthcare neglect in the state is lack of monitoring and evaluation.

“In many cases, projects are launched with ceremonies and media attention, but there are no mechanisms to track progress. Without proper monitoring and evaluation, we cannot link funding to actual performance or impact.”

“And another point is oversight weakness. We lack legislation and all these bodies often lack the teeth to enforce penalties for people who go wrong with mismanaging health budgets. So that’s another thing we should work on. The CSOs and citizens should also be empowered to monitor health projects,” he added.

Gabriel Oke, a public health expert and founder of Medlabconvo, an organisation that advocates for improvements in Nigeria’s healthcare system, agreed with Mr. Jamiu. He added that enhancing the effectiveness of healthcare delivery in rural communities requires providing incentives for healthcare workers. According to him, this can be achieved through improved welfare packages, bonuses, and allowances. Without adequate incentives, it is difficult to attract and retain qualified professionals in remote areas where living and working conditions are less favourable.

This challenge is particularly evident in Sokoto State. According to the MyPHC Report, over 60 percent of PHC staff said there is no mechanism in place to recognize and reward their efforts.

Inside Bagida’s Failing Health Post

Residents of Bagida community in Tambuwal LGA have lamented how the lack of equipment and medical professionals has severely hindered access to healthcare at the Bagida Health Post, the only facility meant to serve thousands in the Bagida ward.

Aisha (surname withheld for fear of victimization), 26, was expecting her first child last year. She arrived at the Bagida Health Post full of hope for quality care, but her experience quickly turned into a nightmare.

“When I got to the hospital around 10:00 a.m., I was already in so much pain,” Aisha said, her voice trembling at the memory. “I kept thinking about my baby and whether we would survive. There wasn’t even a bed to lie on, and no staff in sight. I felt terrified and completely lonely.”

Despite the dire situation, Aisha had no choice but to endure the ordeal, especially since the nearest alternative health facility is located in Tambuwal town, about 30 kilometres away. With the help of her family members and the support of a midwife, she eventually struggled through labour and delivered her baby.

When this reporter visited the Bagida Health Post in March, it is unsurprising why the facility could not cater for Aisha and her pregnancy. The facility stood in a shameful state of abandonment and decay. From the outside, the building’s walls are stained with years of neglect, blackened patches creeping across its fading yellow surface.

The condition is worse inside. Cracks run like open wounds across the walls, and the ceiling panels sag dangerously. The air is thick with dust, and scattered rubbish clogs the corners. Rusty, broken furniture is heaped in a disorderly pile, while torn sacks and filthy plastic containers litter the floor. There are no hospital beds, no basic equipment. Two old mats were seen spread across the center of the facility. The only thing that indicates the place to be a health facility is the tattered medical records scattered on a rickety table.

The Same Result at Ruwa Wuri and Mogonho

When this reporter visited the Ruwa Wuri in March, the facility presented a picture unfit for providing even the most basic medical services. The ceiling is cracked, stained, and a broken ceiling fan hangs precariously. The walls, once painted, are now peeling and discolored, displaying heavy signs of neglect and water damage.

Dilapidated furniture such as broken chairs, a worn-out desk, and an abandoned cabinet are scattered around, adding to the atmosphere of decay. Rusted window bars and shattered window panes expose the interior to harsh weather.

“We do not have enough to accommodate patients, and the few available are broken,”

“We also lack essential drugs and basic medical equipment,”a staff member, who requested anonymity for fear of victimization, lamented the deplorable condition of the facility, calling on the government for urgent intervention. “It is clear the government has not been paying attention to the facility. It is disheartening that we cannot even manage common medical conditions due to the absence of basic equipment. We are pleading with the government to urgently refurbish the facility,” the staff member added.

At Mogonho Health facility, the walls are heavily stained and cracked, revealing years of neglect, too. The floor is bare, dusty, and littered with torn papers and debris.

This centre, meant to serve as a haven for the sick, mirrors the larger systemic failure of rural healthcare delivery. “We only go to the facility for treatment out of no choice, yet won’t still get the desired result,” Haruna Ismail, a resident of Mongho lamented. “We are calling on the government for help. The only available option for us is going to Tangaza town for treatment, and it’s very far.”

In an interview with The Liberalist, Dr. Umar Faruq Abubakar, the Sokoto State Commissioner for Health, reaffirmed the state government’s commitment to improving the healthcare system through the revitalization of health facilities.

Dr. Faruq disclosed that over 166 PHCs and health facilities across the state have been awarded for renovation and revitalization.

“I have visited some of these facilities in Bodinga and Binji to assess the ongoing renovation work. While I noticed some loopholes, I made observations and gave directives to address them,” he said.

He added that upon completion, the revitalized health centres will be fully equipped with the necessary medical equipment and instruments.

Dr. Faruq also highlighted the government’s efforts to address the shortage of healthcare professionals in rural areas through the implementation of adequate policies and strategic postings.

Meanwhile, when contacted, Dr. Larai Aliyu, Executive Secretary of the Sokoto State Primary Health Care Development Agency (PHCDA), failed to respond to multiple calls and messages placed to her phone.

This story was produced for the Frontline Investigative Program and supported by the Africa Data Hub and Orodata Science.