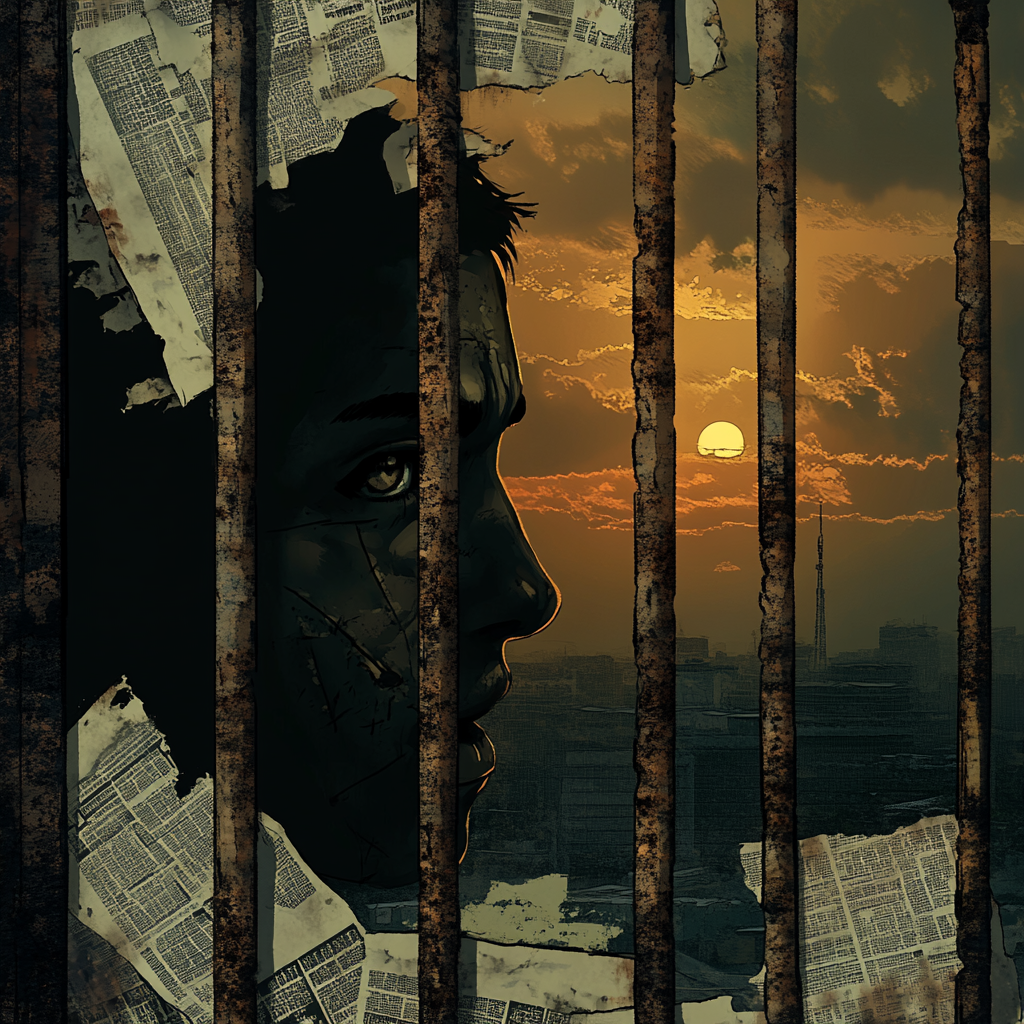

Journalist Dawit Issak’s disappearance of more than two decades epitomises the sorry reality of Eritrea, the world’s most repressive country, where freedom of expression is criminalised. Journalists, top government officials, and citizens who contest government policies either get prosecuted, tortured or disappear at executive behest without a trace.

In its 2024 world press freedom report, Reporters Without Borders says, “Eritrea has become a lawless zone for the media.” Various human rights indices categorise the country as “not free,” a situation that made the country a significant source of refugees globally.

There are more than 600,000 Eritrean refugees and asylum seekers, most of whom would rather endure suffering abroad than return home, statistics reveal. As of mid-2023, Concern Worldwide, a humanitarian agency, discloses that over 537,000 Eritreans, nearly 15 percent of the country’s population, have been displaced abroad due to ongoing violence and political instability.

Citizens like 24-year-old Yonathan Tekle—an Eritrean soldier trapped in Libya while escaping to Europe—described living in Eritrea as hell.

In a phone conversation with pressmen, Yonathan said he would “rather die in the sea than return to Eritrea where hell is awaiting me.

“If I was returned there against my will, I would try to get out again,” he stated.

Experts say Eritrea is a political pariah, a silenced nation, stagnant and isolated from the rest of the world. For this, Eritreans miss out on benefits citizens in other countries enjoy.

In contrast, Norwegians, being in the world’s freest country in terms of press freedom, according to the Reporters Without Border, are a prime example. Norwegians enjoy robust legal protections for freedom of speech, especially in expressing dissatisfaction with government administration.

For instance, the country implemented the Ombudsman Parliament in 1962 to strengthen the frameworks guiding citizens’ freedom of expression. Ombudsman Parliament is an independent body established to safeguard citizens’ rights in their dealings with public administration without political retaliation.

Repressed Press in Eritrea

As free countries like Norway enjoy press freedom, in Eritrea, the best way to share discontentment with the government’s regulations is through a highly censored internet.

Xan Rice, a Guardian correspondent, reported this response when quoting two Eritrean citizens in 2006:

“Don’t call me on this line again. Set up a Yahoo! chat account and we’ll communicate that way… If they hear us talking, they will hunt me.”

“You can’t talk democratically here, or you will end up there.”

Experts’ description of Eritrea as a ‘silenced nation’ justifies its stagnant growth, a result of citizens’ inability to question unfavourable economic policies that impede development. The Heritage Foundation, a research and educational institute, ranks the country 170th out of the 176 countries assessed in its 2024 Index of Economic Freedom.

In a 2016 updated report, Reporters Without Borders reveals that the majority of detainees in Eritrea, one of Eritrea’s most dreaded penitentiaries for prisoners of conscience, are either journalists or citizens who call for government reform. The delayed detention and, in some cases, death of these people is the government’s aggressive response to citizens’ concerns about the state-controlled economy.

President Afwerki’s censorship of citizens’ right to information is despicable. In 2001, the government shut down all independent media and arrested leading journalists. This action forced people to rely on state-owned media outlets that relentlessly propagate President Issak Afwerki’s one-man rule, Human Rights Watch says.

The internet that could have been a good platform to learn and make censorship obsolete is, itself, highly censored, the Committee to Protect Journalists reported. This censorship of Eritreans’ access to information keeps them disconnected from the rest of the world.