The Freedom in Africa Report (FinAR), an index that measures the state of freedom and prosperity, paints a disturbing picture of political freedom across the continent. It reveals that political freedom has been in consistent decline over the past six years.

According to the Report, Africa’s average political freedom score fell from 51 percent in 2020 to 47 percent in 2025, a four-point drop.

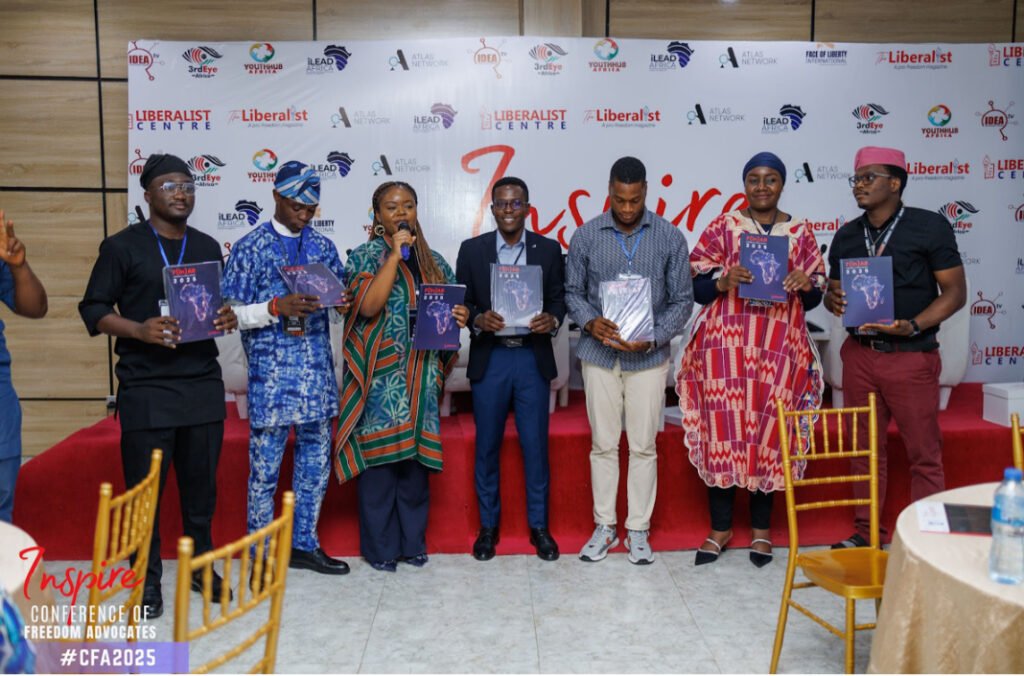

Launched on 25th October at the Conference of Freedom Advocates (CFA) in Abuja, F(in)AR is an initiative of the Liberalist Centre, a policy and research think tank dedicated to advancing liberty and prosperity across Africa. The report offers a continental overview, examining how rights, opportunities, and outcomes interact across Africa’s varied political and economic landscapes.

F(in)AR 2025 evaluates the state of freedom and prosperity across Africa through three connected dimensions: political freedom, economic freedom, and prosperity. While the report did not collect primary or raw data, it drew on trusted, globally recognised datasets that

provide standardised, internationally comparable indicators.

According to the report, indicators were selected based on conceptual relevance, data reliability and coverage, and comparability and transparency.

F(in)AR indexes political freedom on electoral integrity, freedom of speech and expression, press freedom, and freedom of assembly and association. The index also includes judicial independence and protection against arbitrary detention, torture, and extrajudicial killings.

The report notes a sobering state of political freedom across Africa. This decline highlights shrinking civic space, rising state repression, and weakened democratic institutions. Despite frequent elections, electoral integrity averages only four out of 10, as many polls remain marred by irregularities, low voter confidence, and limited accountability. This menace is palpable in many African nations.

For instance, since Nigeria’s return to democracy in 1999, virtually every election has been marred by irregularities such as vote buying, ballot box snatching, result falsification, intimidation, and logistical failures. The persistence of these irregularities is reflected in the high number of contested results. Between 1999 and 2023, over 1,400 election petitions have been filed at various tribunals, challenging outcomes of presidential, gubernatorial, legislative, and local government elections. Nearly every presidential election, including 2003, 2007, 2011, 2015, 2019, and 2023, has been legally contested, underscoring the deep-seated public distrust in Nigeria’s electoral process.

The report also shows severe constraints on freedom of speech and expression. While constitutionally guaranteed in most countries, it is restricted in practice through censorship, surveillance, and intimidation of journalists and activists.

Media freedom averages five of 10, with particularly harsh conditions in war-torn states such as Libya and South Sudan. Freedom of assembly and association, essential for civic activism, scores only 3 of 10, as many governments impose strict registration rules or outright bans on protests and unions. The report notes that these restrictions have eroded citizens’ trust in government and weakened public accountability.

One such instance is evident in Kenya, which scored 38 percent in freedom of assembly on the index. Over the years, Kenya has imposed several restrictions on freedom of assembly, often justified on grounds of public order and security. A notable example occurred in March 2023, when the government under President William Ruto banned opposition-led protests organised by Azimio la Umoja leader Raila Odinga, citing threats to public safety and disruption of economic activities. Police used tear gas, water cannons, and mass arrests to disperse demonstrators, despite Article 37 of the Kenyan Constitution guaranteeing the right to peaceful assembly.

Judicial independence and human rights protection remain fragile pillars of democracy in Africa. The index rates judicial independence at five of 10, indicating persistent executive interference in the courts. The protection against arbitrary detention, torture, and extra-judicial killings is uneven, as some states maintain relative safety. Still, countries like Nigeria, DR Congo, Burkina Faso, and Mali are cited for repression and unlawful detentions.

Nigeria’s record has deteriorated steadily over the decade, with the 2020 EndSARS crackdown marking a significant setback. These abuses underscore the broader trend of states using coercive power to stifle dissent rather than strengthen institutions.

According to the report, Cabo Verde, South Africa, Sao Tome and Principe, Mauritius, Seychelles, and Namibia are among the best-performing countries in terms of political freedom. These countries are cited for maintaining strong democratic institutions, independent judiciaries, free and fair elections, and relatively open media environments.

Carpe Verde is ranked first and the best performer on the Political Freedom index, with an average score of nine out of 10. A notable example that illustrates Cape Verde’s strong political freedom is the peaceful transfer of power following the 2016 general election, when the opposition party, the Movement for Democracy (MpD) led by Ulisses Correia e Silva, won a decisive victory over the ruling African Party for the Independence of Cape Verde (PAICV), which had been in power for 15 years. The election was widely praised by international observers, including the African Union (AU) and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), as transparent, credible, and reflective of the people’s will.

At the bottom of the index are Cameroon, Eritrea, South Sudan, Sudan, and Burundi.

These countries are plagued by prolonged conflict, military rule, or weak institutions that undermine electoral integrity, judicial independence, and protection of human rights. F(in)AR links their poor performance to systemic corruption, repression of dissent, and instability that erodes citizens’ trust in governance. The report warns that without peacebuilding, accountability, and civic reform, these nations risk deepening their democratic decline.