To curtail the mass exodus of medical practitioners seeking greener pastures abroad, the Nigerian lawmakers have proposed a bill to prevent indigenous medical practitioners from being granted full licences until they have worked for a minimum of five years in the country. Though the bill claims to find a solution to the medical brain drain, a mass emigration of doctors in the country, the lawmakers are obviously blind to its potential consequences.

The bill, if passed into law, will not only enslave the medical practitioners in the country by violating their right to freedom of movement under Section 41 and the right to freedom against from discrimination under Section 42 of the Nigerian constitution, but will also bring about a community of jobless doctors in the coming years when the medical practitioners are trapped in the country.

What is even more surprising is that in 2019, the same House of Representatives rejected a bill to prevent public officials from seeking medical treatment abroad. Justifying their rejection, the lawmakers argue that the bill would discriminate against elected officials and it will encroach on their fundamental human rights. If such a bill would violate their rights then the new bill seeking to tie Nigerian medical practitioners down for five years before they could leave the country is also a violation of the medical practitioners’ fundamental rights.

According to Hon. Ganiyu Abiodun Johnson, a lawmaker representing Oshodi/Isolo Federal Constituency and the sponsor of the bill, the amendment is to make quality health services available to Nigerians and that the doctors need to give back to the society before exporting their expertise abroad, given that they received taxpayer subsidies for their education.

The claim by Hon. Johnson for using tax-payers money to train doctors triggered some questions: Are the medical doctors the only professionals who benefit from the said subsidized education, what happens to other fields of study?

Fight the Brain Drain, Not the Doctors

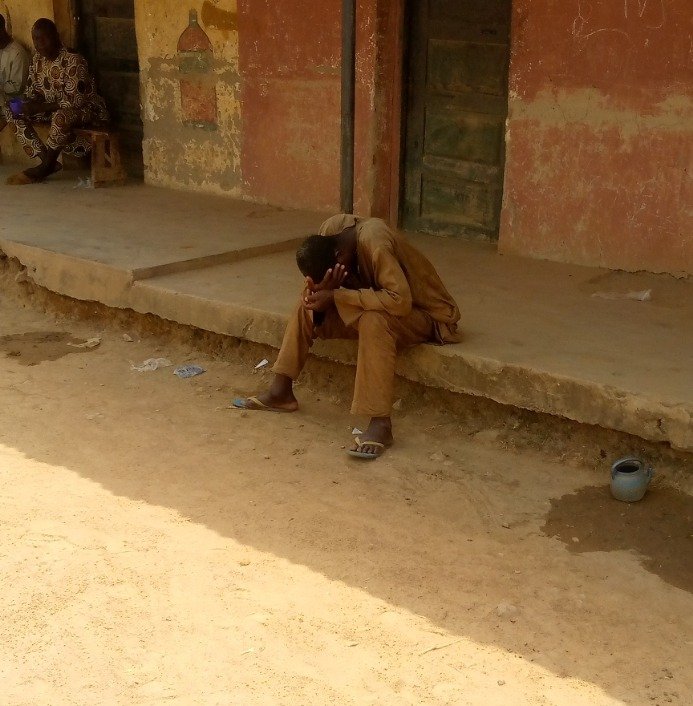

Factors such as inadequate remuneration, poor working environment, insufficient funding, lack of basic training resources and security threats are said to be the major causes of brain drain in Nigeria’s health sector. In August last year, resident doctors lamented the increasing exodus of their colleagues, leaving the country for better treatment. They said six out of 10 doctors have left or are preparing to leave.

The President of the Nigerian Medical Association, Uche Ojinma, said doctors and other health workers are leaving the country for three reasons: poor remuneration, insecurity and lack of job satisfaction. He warned that if the bill should scale through, “we will officially find a way to depart [Nigeria] together. Everybody will go. It is like putting fire to fuel. That is what they will achieve.”

For several times, the doctors have embarked on industrial actions to protest against inadequate treatments, but little to no efforts have been invested to address this. And medical tourism by politicians continues to gulp the nation’s resources. As of December 2022, a report revealed that the Nigerian government spends between $1.2 and $1.6 billion on medical tourism yearly. If such a huge amount is invested in the country’s health sector, maybe the lawmakers would not need to worry about doctors seeking better treatment elsewhere.

It is appalling that the government who demands duty is the same that shies away from responsibility.

The Way Forward

Railing against the proposed bill, Ojinma, described it as a misplaced priority for lawmakers who eat fat on the nation’s revenues. Therefore, he vowed that the doctors would challenge the development in court and through a showdown with the government.

“We will test it in court. Simple. There are international labour laws. Nobody can do that in Nigeria. If it requires going on industrial action to stop it, we will do it, and nothing will happen, he explained. The solution to a problem is finding out the origin of the problem. You find the cause of the problem, and you sort it out. Under international labour law, you do not restrict a worker from migration as long as he did not commit a crime.”

Speaking on how to resolve the challenge of brain drain in the country’s health sector, Dr Ibrahim Oloriegbe, the Chairman Senate Committee on Tertiary and Secondary Health, said it cannot be achieved through this bill but rather, the lawmakers need to address the various factors that make skilled health workers desire to migrate out of the country.

“Rather than enacting laws that will curtail the rights of the citizens to free movement and seek better opportunities, legislators should advocate for an improved system that will be very attractive and make them unwilling to travel abroad to seek better living conditions.”

To revamp the ailing health sector, the government’s legislation needs to look at prioritising private investment rather than tie down the medical practitioners on compulsory labour. As it stands, the bill is still at an early stage, and it is a type that should never see the light of the day.