What if the next great innovator, the next mind poised to reshape Nigeria, is told to wait—not because they lack the ability, but because they haven’t turned 18? This is the practical intention of Nigeria’s minister of education when he announced a compulsory age requirement for tertiary institutions.

In August, Prof. Tahir Mamman, Nigeria’s Minister of Education, announced a controversial policy that would take effect in 2025: candidates under the age of 18 will no longer be allowed to sit for the Senior Secondary School Examination (SSCE) and Unified Tertiary Matriculation Examination (UTME). According to the minister, this decision is rooted in the Universal Basic Education Act, and the goal is to standardise the age for entrance into tertiary institutions across the country.

The problem is that a close examination reveals serious flaws in both the rationale and potential consequences of this policy, which disregards the diverse educational needs of students and poses a significant threat to equal access to higher education. In a country where time is already a precious resource, this policy threatens to sideline the students who are ready to excel.

Mis–reading the Universal Basic Education Act

The foundation of this new policy is questionable. The Universal Basic Education (UBE) Act of 2004, as referenced by the minister, does not prescribe any age limit for students accessing higher education. Instead, it focuses on guaranteeing universal access to basic education. The act is part of Nigeria’s commitment to global education protocols, aiming to ensure that all children, regardless of socioeconomic background, have access to basic education.

Thus, by imposing an age limit on access to SSCE and UTME, the government is veering away from the spirit of the UBE Act. Instead of expanding educational opportunities, this policy narrows them, limiting students’ access to tertiary institutions based on arbitrary age criteria rather than academic readiness.

Unintended Effects

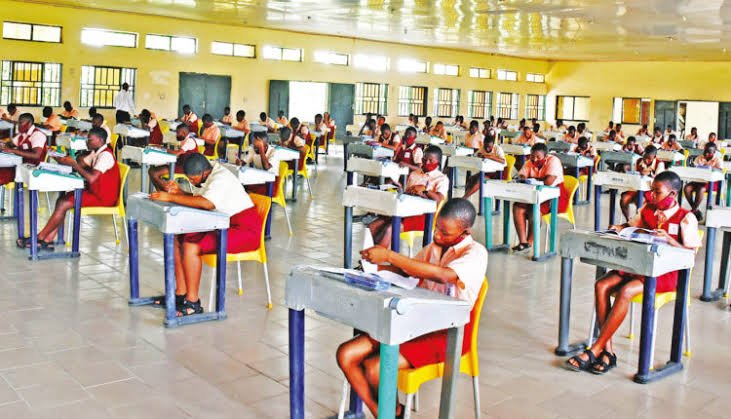

One of the most troubling aspects of this policy is its failure to recognise individual differences in intellectual development. Requiring students to be at least 18 years old to sit for university entrance exams penalises precocious students who might be academically ready for higher education but do not meet the age requirement. It neglects the unique talents of young geniuses, some of whom might be ready for university long before they turn 18. These students, who have worked hard to meet academic standards, will be unjustly disqualified from pursuing their higher education goals.

For example, if there were such restrictions in the United State, there would not have been Michael Kevin Kearney, a US born who became the youngest person to attend college at the age of six and graduated with a degree in geology by the age of ten.

This contradicts the core principle of merit-based access to education, enshrined in Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states that “higher education shall be equally accessible to all on the basis of merit.”

In a country like Nigeria, where federal universities are already plagued by frequent strikes and delays, this policy could exacerbate the problem of late graduation. A student admitted into a university at age 19 or 20 may face additional years of delay due to institutional disruptions, such as industrial actions, making it even harder to meet age requirements for certain job opportunities. Also, applying this policy on courses that require post-graduate qualifications like law or clinical psychology, and those with longer years of study like medicine will put students at a disadvantage.

In fact, the assumption that age is a reliable measure of maturity is misguided. Though, generally, maturity has been linked to age, studies have shown that it is also influenced by a range of factors, including life experiences, education, and exposure to different environments. To equate maturity solely with age is a simplification that does not reflect the complexity of human development.

Another critical issue is Nigeria’s low life expectancy currently estimated at 56 years. By pegging the age of university entry at 18, the government leaves students with only 38 years to complete their education, establish a career, and fulfill their dreams. This limited time frame becomes even more constraining when one factors in the frequent delays in Nigeria’s education system. The pressure on young people to succeed within this limited time is both unrealistic and unfair.

The age peg policy introduced by the Ministry of Education is retrogressive and counterproductive. Instead of fostering an inclusive, merit-based education system, it places unnecessary restrictions on young Nigerians, limiting their ability to pursue higher education and ultimately affecting their future career prospects. With the new policy, Nigeria’s minister is asking the country’s future to wait.

Oluwaferanmi Bello is a Journalism for Liberty Fellow at the Liberalist Centre.