Ahmad Shuaibu’s life took an unexpected turn at just one year old. As an infant, his legs would stiffen violently, foam would gather at his mouth, and he would collapse in eerie silence before slowly regaining consciousness.

These episodes returned daily, pushing his worried parents, who live in Wamba, a community in Nasarawa state, north-central Nigeria, to seek help at the local primary health centre. Though the nurses prescribed drugs and assured them it was nothing serious, the convulsions persisted. Frustrated, his mother took him to the Wamba General Hospital, but his condition could only worsen.

For years, the family shouldered the financial and emotional burden of his care. But shortly after his 18th birthday, his father died, and the responsibility fell solely on his mother. Not long after, the mother learned the hard truth: Shuaibu suffers from epilepsy, a disorder marked by involuntary movement, convulsions, and loss of consciousness. His mother sought help and support till the moment she too passed away last year.

Now an orphan, Shuaibu walks and falls with ceaseless discharge of convulsions as his sickness grows with him.

“We went to the hospital many times again. They later advised us to seek herbal medicine. Having access to the medicine is not easy. They told us to bring goats, and we did. They told us to bring a duck; we did, but still, there was no improvement,” Shuaibu’s stepmother Ramatu Usman told The Liberalist.

Mrs Usman, who was also approaching her twilight, was the one who embraced the now 28-year-old orphan Shuaibu, taking care of him and boiling his herbal medicine, which remained the only option she could afford. “We paid a large amount of money all the time for his medication until he grew into adulthood,” she said.

Right from his childhood, nobody thought of taking Shuaibu to school because of his illness and lack of money for medication. His brain, to his guardians, is unfit for learning due to unsteady comprehension and incessant breakdown of consciousness.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), epilepsy is a chronic non-communicable disease, affecting 50 million people in the world, causing seizures due to electrical discharges in cells of the brain, resulting in convulsions and jerking in the whole body. The symptoms and their long-term effects on a person make it one of the most dangerous disabilities in human beings.

A survey by the National Library of Medicine put the number of people living with epilepsy in Nigeria at over 1.2 million. Many of these patients live and die with the illness. Some rely on local herbal medicine as they couldn’t even afford to pay the bills for medical treatment that could reduce the growing damage caused by the disease.

This remains a significant burden to the country, as lack of support and limited financial resources render many victims helpless and vulnerable.

Dr Onwusobalu Somto, a senior medical expert at Wamba General Hospital, describes epilepsy as a “dangerous neurological disorder”. “It causes episodes of involuntary body movement and is sometimes accompanied by loss of consciousness and control of bowel or bladder function,” he said

At its high tempo, he noted, it strikes unexpectedly, causes convulsions, and forces a long sleep as the victim loses consciousness. The illness becomes worse in the absence of care and medication. Parents are always caught up in worries about their wards’ safety, who might fall at any moment or place. Sickness is likely to strike during sleep, at work, or while travelling.

“There are many possible causes of epilepsy, including an imbalance of nerve-signalling chemicals called neurotransmitters, tumours, strokes, and brain damage from illness or injury,” he explained.

But, just like many medical conditions, epilepsy can be controlled and managed, reveals Dr. Somto. To treat the disorder, “few approaches are attainable in our environment, which is mostly medical and surgical treatment aimed at managing the aetiology or the cause of the epilepsy in an individual,” he said.

Comprehensive treatment comes with a price tag. Unfortunately, without sustaining funds, not-so-privileged people with the neurological disorder wander in destitution and perpetual suffering. Most of them fall and rise on their own and continue suffering till the end of their life.

For Dr. Somto, epilepsy is a daily battle that too many people are forced to fight alone. Governments and NGOs, he argued, should be on the front lines, creating policies that lower the cost of care, guarantee a steady supply of affordable medication, open the doors to specialised treatment, and teach communities the basics about epilepsy.

“I believe the government knows what to do; most government officials travel overseas to access care. So the government should take a page from the book of those nations,” he said.

The Nigerian Disability Rights Act 2018 describes persons with disabilities as those suffering from “mental, intellectual, or sensory impairment”. The act offers support and opportunities, and protects the rights of persons with disabilities. Nonetheless, findings reveal that epileptic patients in Nigeria, despite suffering from mental and intellectual impairment as stated in the law, are neglected, denied proper support and medication in many hospitals.

Government efforts to address disability rights have repeatedly fallen short. For instance, in 2019, former President Muhammadu Buhari established the National Commission for Persons with Disabilities (NCPWD) to protect the rights of people with disabilities. The commission was formed under the Persons with Disabilities Rights Act of 2018. But despite the law and government’s promises, people with epilepsy remain visible on the streets, living in poverty, and stripped of equal opportunities.

While research by the International League Against Epilepsy confirmed Dr Somto’s submission that epilepsy can be treated, it reveals that many primary healthcare centres and teaching hospitals in Nigeria either lack the specialists required for the treatment or the facilities to undertake the procedure. This appalling condition in the healthcare system affected epileptic patients like Shuaibu, whose parents were told by the nurses to seek herbal medicine.

The study further reveals that only two teaching hospitals in Ibadan and Lagos have facilities for training epileptologists, medical specialists who diagnose, treat, and manage epilepsy and related seizure disorders. But that’s all to it. In relation to treatment, no facility in Nigeria currently offers epilepsy surgery, leaving those in need to either seek treatment abroad at great personal cost or suffer without care.

Convulsion Amid Endless Suffering

The challenges of individuals living with epilepsy always become more severe when no one seems to care about their existence. They live in loneliness, consistent regret and persistent shame. Whenever they fall, after regaining consciousness, some wait until people have dispersed before standing up and leaving.

For example, looking at Shuaibu’s face would rend one’s heart with deep sorrow. His face is dotted with healed wounds. As an adult, he could not work to earn money and fend for himself. Anytime he tried to do so, it would be detrimental to his well-being.

Coincidentally, on Wednesday afternoon in January 2025, in the presence of this reporter, Shuaibu was seen lying flat on the ground after his illness struck him on the road. His wheelbarrow, full of waste, was visible behind him. He had been sweeping the street to earn something from the shop owners. However, after he packed the waste in his wheelbarrow, his convulsions started, leading to a gripping seizure that caused him to fall on the pot of dirt he was pushing and roll on the floor.

The midday sun was unforgiving, beating down on the dusty street where Shuaibu lay. Sweat trickled down his face, mixing with the streaks of saliva that clung to his mouth and nose. His clothes were stained, and his body coated in grime. A few passersby slowed their steps, their eyes lingering for a moment before moving on. Others kept their distance, casting quick, uneasy glances and shaking their heads. No one bent down or reached out a hand. The heat wrapped around him like a shroud, and he lay there, trapped in his seizure, while the world carried on.

At home, his stepmother was not surprised or moved by the urgency to rescue him. “It’s not every day,” she said, her voice resigned. “It’s monthly. Around the 5th or 6th, we know it’s coming. Then he falls. And when the next month comes, it happens again. He will fall.”

According to her, the reaction comes whenever he starts laughing alone. If he’s standing, he starts convulsing. Later, he goes down, and foam of saliva comes out of his mouth.

“He will lie down sometimes. Even if you are talking, he will not hear you. He will lie on the ground until the whole thing stops before he wakes up,” she explained.

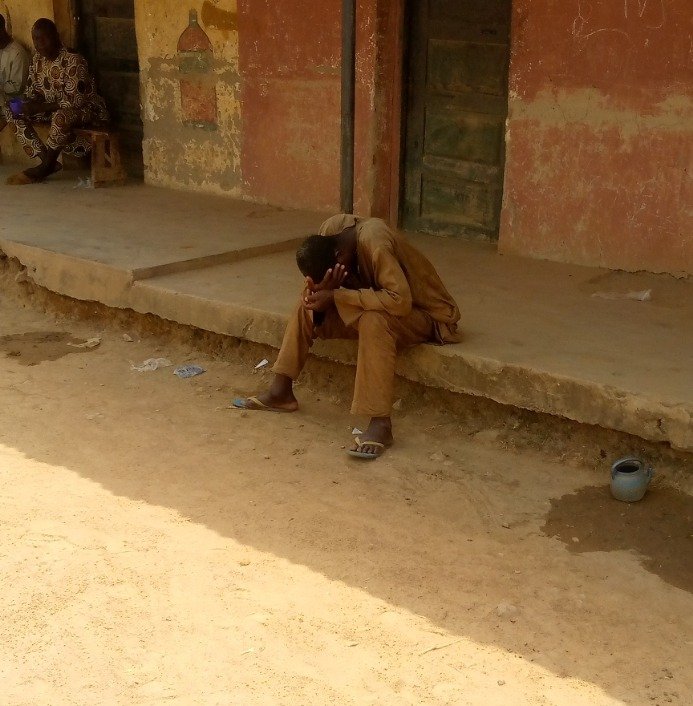

When Shuaibu finally woke up, he sat several feet away from people and clutched his face with his hands. Alone. His ankles appeared swollen. When he walks, he limps due to the multiple injuries he sustained from his fall. He could feel the discomfort more in his right leg.

The Travails of Salihu Umar

Salihu Umar, a resident of the Wamba community, has been battling the disease for many years. At 7 years old, Umar began spitting saliva onto the ground. Any clothes he wears would be drenched with saliva. His parents thought he would stop when he grew up. But strangely, as he grew, the sickness began to show. He would fall after convulsing, then became unconscious.

Now, at the age of 28, Umar had lost all his front teeth after falling many times. To cater to his medication, sometimes he followed relatives to give him money. However, when he was unconscious, people would search and steal the money. His aunt, Chindo Liman, who became his guardian after he lost his parents, revealed that all their efforts to cure him were in vain.

“We tried our best, but it didn’t work out for him. Sometimes, if I travel and hear there is a cure, I would try to get it to see,” she said. “I tried Islamic clinics, hospitals, and herbal medicine. And he is always trying to take his medication. But it’s not working,” she added.

Liman recounted Umar’s worst fall in the mosque, when he fell into a well. “It shocked everyone when he was found dipping inside the water. People thought he wouldn’t survive it. But he was saved thereafter,” she said.

Like Shuaibu, Umar routinely loitered around pap sellers to get leftovers from customers. His beggarly condition and haggard look sometimes make children throw stones at him or make fun of him. When they provoked him, he reacted and racially abused them.

“What bothered me a lot was that he used to fall badly. Sometimes you will just see a big wound on his face,” Umar’s aunt, Liman, told The Liberalist.

Rejected and Forgotten

In the Wamba community, Danlami Adamu, who also grew up without parents, is another unfortunate child who has epilepsy. His aunt got tired of his constant convulsions and medication before sending him back to his family’s house.

Faced with reality alone, Adamu resorts to self-help measures. Every Monday and Friday, he goes to the market with his wheelbarrow to carry people’s loads and earn money for his medication and other needs. He says that most of the time, he buys two medicine cards at the rate of ₦700 each and that’s the only cheap medicine he can afford.

Nonetheless, just like any other patient who has epilepsy, sometimes he pays the price for his hustle whenever the illness strikes him at the market.

Among the patients interviewed by The Liberalist, only Adamu could speak for himself about the distress and depression he endured as a result of his illness. Others hardly talk steadily or comprehend simply due to the severity of their illness.

“You see, I have been suffering from this disease for a long time. Even if I take medicine, it used to rise again. Sometimes it rises before I can get the medicine,” he said.

On his left elbow, a big wound never seemed to heal. This reporter discovered that whenever Adamu was attacked by the illness and started freezing, he would drag and bruise his left elbow on the ground till it started bleeding. That was the reason it never got healed.

Now, he says nothing worries him more than the inability to keep going to school. He grew disenchanted with life, as those who once raised him or promised to sponsor his education no longer wanted him. His incessant seizure became the sole factor; people around him consider his schooling a waste of time. No one seems interested anymore.

Through his voice, the sudden anguish reflected the countless disappointments he faced trying to follow people to teach him how to read and write. “I told them to enrol me in school, but they refused, telling me that my illness would not allow me to learn, and it would scare children away from me,” he narrated.

Despite graduating from Ta’al Model School, a primary school in the Wamba community, he still couldn’t read or write. This became Adamu’s source of worry, adding that he experienced convulsions many times in primary school; in class, on the assembly grounds, and during break time. “Children run away from me every time my sickness rises,” he said.

Far from being saved, Adamu and many other victims of epilepsy, both young and adult, who couldn’t complete their education, add to the large numbers of out-of-school children in Nigeria. According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), as of 2024, over 10 million children of primary school age and 8 million children expected to be in secondary school are out of school, exposing the country to the risk of widespread illiteracy.

However, unlike Nigeria, some countries like the United Kingdom (UK) find a way to tame epilepsy. There, victims receive proper support, and medication is always available. There is also an available channel where every patient or their relatives can access urgent help by contacting agencies responsible for assisting patients in need.

A Futile Search For Cure

At 11, Mahmud Aliyu, a resident of Nasarawa state, fell from a mango tree. His parents initially thought it was a normal fall, not knowing that it was epilepsy that caught up with him. By the time he regained consciousness, he began to cry out due to the overwhelming pain he felt in his back. After multiple scans, the doctor found that he had sustained an injury. Then he was given medication before he returned home with his mother.

In the next few days, Aliyu followed his elder brother, Suleiman Aliyu, to a barbershop. They were sitting close to each other when the young Aliyu began to stare blankly at the horizon. When his elder brother tried to hold his hand, suddenly, he started convulsing before slipping down from his sitting bench.

“I thought he was looking at a butterfly, but suddenly he fell. That was the first time I noticed his convulsion. Then we later discovered it was epilepsy. I find it very strange,” his elder brother Aliyu said.

To salvage Aliyu from the strange disease that brought fear to his family, his mother, though financially down, and her husband, who was bedridden with a stroke, vigorously searched for a cure from the nearby hospitals and herbalists around the community. However, her search yielded no results. She only got a precautionary pill, which provided only a temporary solution.

“Our parents took him to many hospitals. They told us they couldn’t find the problem,” Aliyu’s elder brother said.

Poor Health Care Service in Rural Hospitals Leaves Epileptic Patients in Misery

In June 2025, The Liberalist visited rural hospitals in the Wamba community, where Shuaibu and other patients were once taken for treatment. Nasiba Adam, a midwife at the Model Primary Health Care Wamba, stated the primary health care in the community has no experience or medication to treat or adequately manage epilepsy. She revealed the facility “can’t manage epilepsy here because there are no facilities, no proper medication to give them,” said Adam.

“The big problem is that you must look for a professional specialising in the treatment because the illness touches the brain. Not every medical worker can manage epilepsy. That’s why we can’t even manage or treat them here,” she said.

The shoddy condition of the primary health care, which is devoid of workforce and medication for epilepsy patients, left the nurses with the only option of cheap first aid. Whenever the convulsion started and the epileptic patients were brought to the hospital, Adam and her colleagues would lay them in an open space and put a spoon in their mouth to protect them from biting their tongue.

When the seizure increased, the nurses would remove any dangerous objects beside them on the flat surface nearby. From then on, the patients would roll their bodies. Later, when the reactions subsided and they woke up, Adam and her colleagues would give them analgesics like paracetamol (PCM), Diclofenac, and Boskopan injection to ease the pain in their bodies.

Adam revealed that they refer the patients to a general hospital in the community after offering what they can give.

Because the primary healthcare centre is the first point of contact for most epileptic patients and because it is the most affordable, Adam said the only way to help is for the government to host training for nurses at rural primary health care, which will be handled by a professional specialising in the treatment of epilepsy.

“Only if someone is being trained will we have the knowledge to handle this case. It’s not everybody in the medical line that has the skills to treat epilepsy patients,” she said.

At the Wamba General Hospital, which is the last resort to epileptic patients in the rural community after referral from the primary healthcare centres, the nurses told The Liberalist that they could not offer any treatment or tame the illness with better medication. Their situation left them no different from what the patients face at the PHC.

Lilian Agushaka, a chief nursing officer at the general hospital in Wamba, said epilepsy is not exempt from medical conditions, but since it affects brain function, they categorised it as psychiatric, a unit the hospital does not have.

According to Agushaka, the general hospital also lacked equipment and doctors who specialised in the treatment of the disease. Like primary healthcare centres, Agushaka and other nurses relied on pain relievers like diazepam and paracetamol after the patients sustained injuries during the crisis. “When they get injured, we give them a tetanus injection,” she said.

Billions Going Down the Drain

While rural hospitals remain poorly equipped, the Nasarawa state government has continued to allocate billions to the Ministry of Health in recent years. In 2023, the ministry received ₦18.61 billion, followed by ₦27.5 billion in 2024, and ₦36.20 billion in 2025.

At the federal level, the pattern is similar. A search on BudgIT’s GovSpend shows that the Federal Ministry of Health was allocated ₦243.48 billion in 2021 and ₦252.34 billion in 2020. Allocations grew to ₦405.79 billion in 2023 before dropping slightly to ₦373.64 billion in 2024.

Under the same ministry, the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA), an institution tasked with supporting PHCs across states and local governments, has also received steady funding. In 2021, it was allocated ₦29.97 billion, followed by ₦35.79 billion in 2022, ₦38.63 billion in 2023, and ₦38.31 billion in 2024. Yet many primary healthcare facilities remain dysfunctional and unable to provide even basic treatment for epileptic patients.

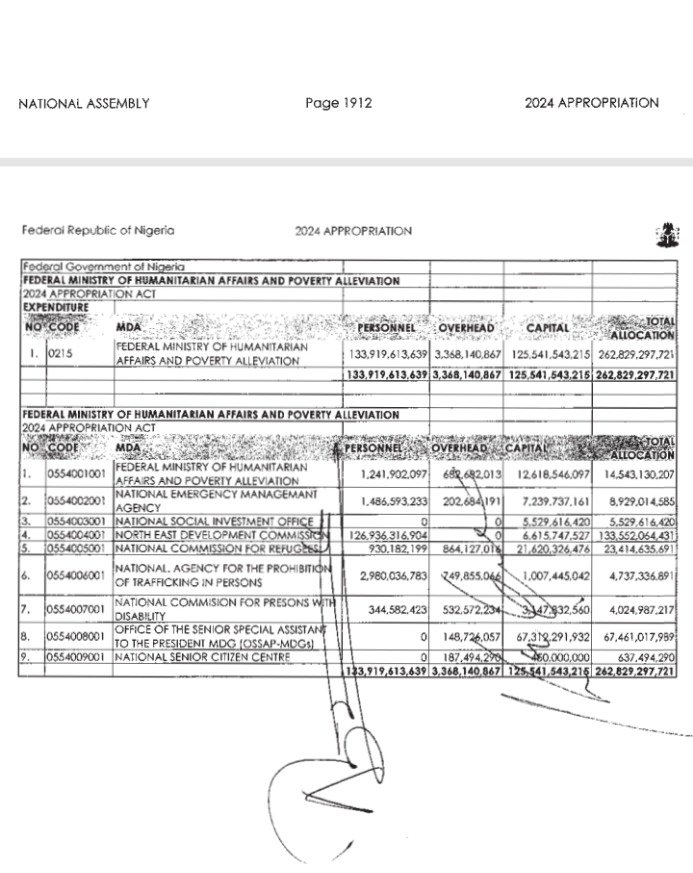

In December 2024, the Federal Government announced plans to unveil an allowance for persons with disabilities, allocating ₦4 billion through the Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs. But as of the time of writing, none of the epileptic patients interviewed for this report had received any support.

Months later, in June 2024, Punch reported that the federal government increased this allocation by 500 percent, far above the initial December release.

In another report, Executive Secretary of the NCPWD, Ayuba Gufwan, said the funds were meant to support persons with disabilities by covering medication, care, education, and other basic needs. “This move underlines the need to fund scholarships, provide mobility aids, reconstruct accessible office facilities, and expand medical outreaches. We also believe that PwDs have a right to live an equal life and have equal opportunities with persons without disabilities, and we intend to stick to these missions,” he said.

However, despite bold promises and huge allocation of funds, people with disabilities and epileptic patients are neglected amid trials of hardship and lack of medication in Nigeria.

In an interview with The Liberalist, Dr. Gaza Gwamna, the Nasarawa state commissioner of Health, said the state was not aware of the situation in the primary healthcare centres. He then referred the matter to Dr. Peter Attah, the state’s Director of Public Health.

After reaching out to Attah, he promised to get back to this reporter but failed to do so, despite several reminders.

Also, all efforts to reach the National Commission for Persons with Disabilities via call, email and text message were unsuccessful.

“It’s a lot of money,” cried Ramatu Usman, Shuaibu’s caregiver, making reference to what she has spent to take care of Shuaibu. “We need proper medical support because we have no money or strength to bear the responsibility again.”

________

This report was produced as part of the HumAngle’s Strengthening Community Journalism and Human Rights Advocacy (SCOJA) project, supported by The Kingdom of Netherlands Embassy in Nigeria.