The United States President Donald Trump recently unveiled a controversial tariff policy, imposing hefty duties on exports to the United States. But international trade experts warn the development could disrupt global trade and deal a heavy blow to emerging economies.

Though countries like China are ready to go on a trade war with the United States by imposing retaliatory measures, African nations with their significant history of trade relations with the U.S., could only brace for the effects of the new tariffs.The hardest hit in Africa is Lesotho, slammed with a 50 percent, one of the highest on all countries, second only to China with 145 percent.

Already a major exporter of denim materials used in the American fashion industry, Lesotho recorded a trade surplus of over $234 million with the U.S.

While President Trump claimed the new tariff is a reciprocal reaction to tariff imposed on the United States exports to the rest of the world, Mokhethi Shelile, Lesotho’s trade minister, said the data leading to such conclusion is not based on facts.

“We are a small economy,” said Shelil. “We just have to speak to the U.S. administration.”

Announcing the tariffs during a speech at the White House Rose Garden, President Trump admitted the measures are a historic pivot from the free-trade orthodoxy that has guided the global economy since World War II. Notwithstanding the successes attributed to the free trade the U.S has adopted for centuries, he argued the new tariffs are necessary to protect American jobs and industries from what he described as unfair foreign trade practices.

“This is one of the most important days in American history,” said Trump. “We will supercharge our domestic industrial base. We will open foreign markets and break down foreign trade barriers, and ultimately, more production at home will mean stronger competition and lower prices for consumers.”

For instance, President Trump says Nigeria imposes a 27 percent tariff on U.S. exports; in retaliation, he slammed a 14 percent duty on all the country’s exports to the U.S. Experts are raising concerns that Trump’s decision marks a shift away from trade liberalisation principles in Africa, like the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), a trade agreement enhancing market access to the U.S. for qualified Sub-Saharan African countries.

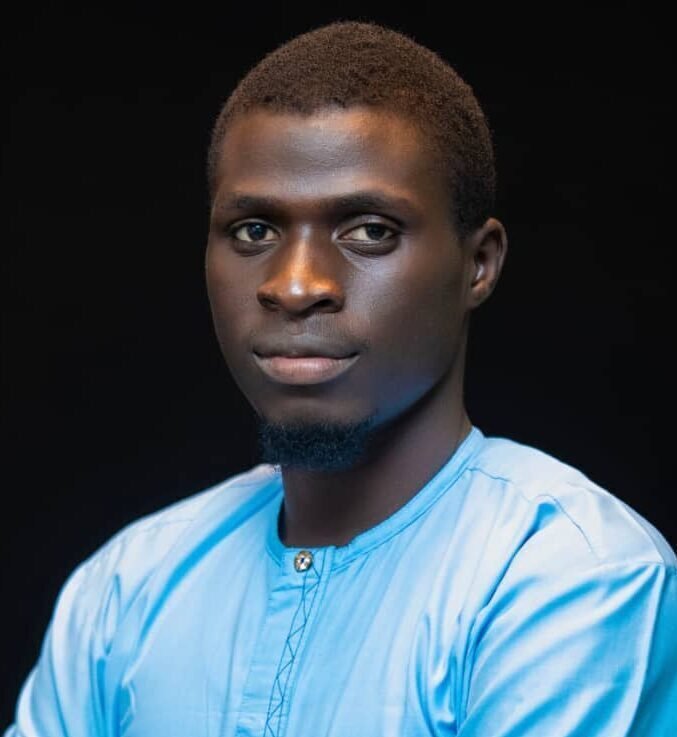

Dr. Jumoke Oduwole, Nigeria’s trade minister, says the tariffs would hit hard on the Nigerian exports, particularly on the oil sector.

Nigeria’s exports to the U.S. average between $5 and $6 billion annually, with crude oil making up the vast majority of this trade. Oduwole says the policy will increase consumer prices, weaken the standard of living, and slow down manufacturing. Most critically, she said it could hinder international trade and reduce demand for Nigerian oil in the global market.

While oil continues to be at the forefront of Nigeria’s exports, agricultural products like live plants, flour, and nuts account for about two percent of total exports. Experts believe these non-oil products, once covered under the AGOA, face new threats from Trump’s protectionist policy. Specifically, the trade minister noted, a new tariff on key categories may impact the competitiveness of Nigerian goods in the U.S. “For businesses in the non-oil sector, these measures pre-destabilise challenges to price competitiveness and market access, especially in emerging and value-added sectors vital to our diversification agenda.”

The minister’s concern stems from Nigeria’s record as a top US importer and exporter. In fact, in 2022, Nigeria ranked as the second-largest destination for U.S. exports in Sub-Saharan Africa. In 2023, it exported $6.29 billion worth of goods to the U.S. while importing just $3 billion, resulting in a trade surplus of more than $3 billion, according to the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC).

Another African country, Madagascar, faces a 47 percent tariff on key exports like vanilla and apparel, while countries like Algeria, Angola, Botswana, Libya, Mauritius, and South Africa received tariffs well above 30 percent.

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa faults the new policy as “punitive” and “a barrier to trade and shared prosperity.” The administration says it is high time the country pursued a new trade agreement with Washington to protect long-term commercial ties.

In a turn of events, as African countries brace for Trump tariffs, President Trump announced a 90-day pause on all the reciprocal tariffs, save China. Meanwhile, economists are raising concerns that the tariff policy, if resumes, would also hit hard on the U.S economy. By taxing all imports, they warned, U.S. businesses would be paying more, ultimately prompting them to raise prices for consumers.

“It will be difficult for the U.S. to avoid a recession if the tariffs stay at the level that’s been announced,” said Claudia Sahm, Chief economist at New Century Advisors, a U.S based financial consultancy.

According to Kristina Fong, an economic affairs researcher at ASEAN Studies Center, U.S. manufacturers and importers will be the first to feel the effects. Fong says if American importers choose to absorb the cost of the tariffs, their profitability decreases, leading to changes in businesses’ cost structures, such as downsizing operations and laying off workers.

For countries that may choose to retaliate against U.S. tariffs, such as China, Fong continues, U.S. imports into those countries would likely face a similar process, resulting in reduced demand for American products, especially those assembled using components sourced from other nations.

Michael Strain, an economist at the American Enterprise Institute says the new tariffs on other countries constitute a tax increase of 400–500 billion dollars this year on American households and on businesses.

“The combination of a big increase in taxes and the tariffs would increase the prices of these imported goods that households face [and] would mean that households would very likely see negative income growth,” said Strain. “That alone would risk a recession in the U.S.”