In theory, local government in Nigeria is designed to be the closest tier of governance to the people, fostering development, accountability, and grassroots democracy. In practice, it is the state governors’ political machinery—tools for patronage and personal enrichment.

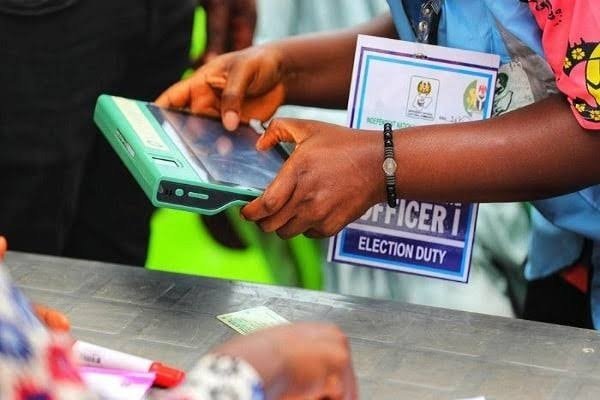

For many years, despite constitutional provisions establishing local government as the third tier of government, state governors routinely relegated this branch, failing to conduct elections and instead appointing loyalists as caretaker committee members. In August, however, the Supreme Court reaffirmed the autonomy of local governments, mandating that funds be transferred directly from the federal government to their accounts. The ruling also made elections for local government administrations compulsory.

Nevertheless, local government elections across the country remain heavily influenced by state governments. In nearly every instance, the ruling party in the state sweeps all local government chairmanship and council seats, raising serious concerns about the integrity of the electoral process and the prospects for genuine grassroots democracy.

Sokoto State offers a textbook example. In the recent local council elections, the governor’s party (All Progressives Congress) won all 23 chairmanships and 244 councillor seats. In a state where the APC barely secured a narrow victory in the last year’s governorship race, this raises an obvious question: did the electorate undergo a sudden and radical shift in party loyalty? The answer, of course, lies in the governors’ unfettered influence over the electoral process.

A similar scenario played out in Nasarawa State, where local government chairmen and councillors were effectively selected rather than elected. The ruling APC claimed all 13 local council chairmanships and 140 councillorship seats, leaving only seven to opposition parties. This near-total dominance underscores the sitting governor’s influence as the APC flagbearer. Predictably, the elections were met with widespread contempt, creating an atmosphere of tension and deepening distrust among the people in the state.

In 2024, at least eleven governors ignored court orders to hold proper local government elections, and where the elections were held, as witnessed in Sokoto and Nasarawa, their parties swept the polls. Four governors delayed the process, setting token dates with no assurance of transparency.

At the heart of the problem is the State Independent Electoral Commission (SIEC), which oversees local council elections. Far from being independent, SIECs are controlled by state governments, which use them to stage-manage elections and ensure predetermined outcomes.

Therefore once installed, local officials are little more than rubber stamps for the state governor. Council chairmen are often selected for their loyalty, not competence, and councillors exist merely to nod along to the governor’s agenda. Their supposed mandate—to deliver essential services such as infrastructure, education, and local security—is ignored.

In all this, two illegal practices dominate: conducting sham elections and arbitrarily appointing or dissolving local government cabinets. In Rivers State, Governor Siminalayi Fubara dissolved all 23 local government chairmen in a single day in 2023. His action, a brazen affront to democratic norms and the rule of law, epitomises the disdain governors show for grassroots governance. Such abuses mock the constitutional promise of local government autonomy and deepen public cynicism about Nigeria’s democracy.

The consequences for ordinary Nigerians are that local councils, meant to be the engine of grassroots development, eventually become perpetually idle. Community schools are neglected, roads go unrepaired, and local economies stagnate. For many Nigerians, the idea of local government as a functional entity is a distant memory.

The broader political ramifications are equally troubling. By sidelining opposition parties and stifling competition, governors erode the foundations of democracy. Local elections, far from serving as a barometer of public opinion, become exercises in consolidation for ruling parties. This dominance stunts political diversity and breeds complacency and corruption.

“When local government representatives are selected rather than elected, they are accountable only to the state governors or political elites who place them in power rather than the people they are expected to serve,” a coalition of civil society organisations working on anti-corruption and good governance in Nigeria noted.

“Elections should reflect the genuine choice of the people. We demand strict compliance with established electoral procedures, including ensuring that results are based on actual votes cast at polling units.”

The coalition stressed that the current structure of SIEC grants state governors irrevocable impunity for the control of local government elections. This, among others, calls for the adequate reform of the electoral process in order to foster progress and development of grassroot communities.

Fixing Nigeria’s local councils requires nothing short of a political revolution. It needs autonomy for local government—not just on paper, but in practice. While INEC is far from perfect, it is even a more credible electoral body than the state-controlled SIECs.

For now, despite recent autonomy confirmed by the Supreme Court, the fraudulent elections continue to render local government in Nigeria a hollow institution—neither democratic nor developmental. Unless the stranglehold of state governors is broken, millions of Nigerians will remain underserved, trapped in a system that exists to serve a selected few rather than all.

Usman Yakubu Usman is a freelance journalist with keen interest in social justice, good governance and egalitarian society. His works which appear on national and international media outlets, cover economy, education, health and environment among others. He is a 2024 Journalism for Liberty fellow with the Liberalist Center, a pro-freedom think tank promoting liberty and prosperity in Africa.