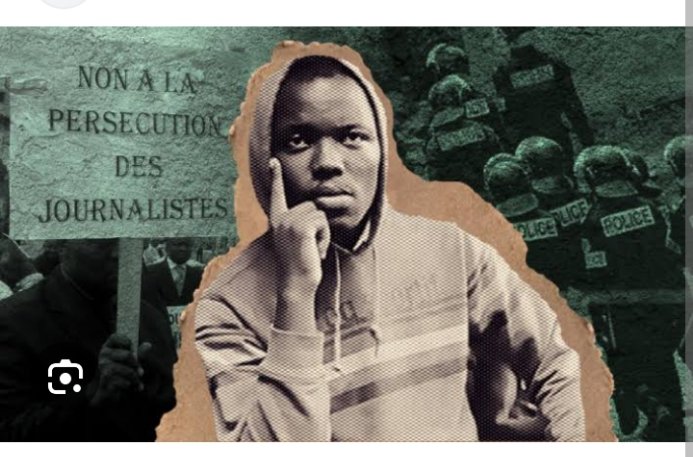

Each day behind bars stretches into a blur for Tsi Conrad, the Cameroonian journalist who once believed his camera could change his country. Now, hope, though alive, feels like a distant memory.

In December 2016, when Cameroonian police started raining bullets on a group of protesters in Bamenda, killing four in the process, Conrad brought out his recording gadget and began filming the protest. But it was not long before the police found him, gave him the beating of his life and bundled him into the car.

“The police seized and destroyed my camera and tortured me into signing a false confession,” said Conrad, in a prison note published by the Freedom House.

He later appeared before a military tribunal, which sentenced him to 15 years imprisonment. As of 2025, Conrad has already spent six years in custody, with nine more years to complete his term.

“It is widely recognised that my detention is nothing more than retaliation for my reporting,” writes Conrad.

Haunted by the unfair sentence, the journalist demanded justice, calling for accountability against the Cameroonian government for its authoritarian behaviour and sabotage of the rule of law.

Before his arrest, civil unrest in the form of protest broke out in Cameroon due to the government’s resolve to impose French in schools, courts and other official institutions instead of the widely accepted English language. Many citizens see the French language as a barrier to their education and development. Media reports show that large numbers of students in schools find it difficult to speak French. This limitation severely reduces their chances of getting jobs.

Security forces brutally attacked protesting students from various schools. At the height of the protest, a video record shows Cameroonian police in Buea town, a central capital city of Southwestern Cameroon, maltreating female students on the streets.

While the government deployed security forces to disperse the crowds, massive protests led by teachers and lawyers against the contentious language policy filled the streets, resulting in widespread arrests, beatings, and detentions.

A report by Amnesty International says no fewer than 100 Cameroonians were arrested and detained during the protest as of 2022. One of them was a 29-year-old trader, Intifalia Oben, who spent five years in prison after facing charges of rebellion. Authorities used the same charge to convict and sentence Awasum Mispa Fri, an international lawyer and the president of Women of the Cameroon Renaissance Movement (MRC), to seven years imprisonment. Another protester, Mancho Bibixy Tse, a local journalist from Bamenda city in northwestern Cameroon, who took a leading role in the demonstration, bagged a 15-year sentence.

Meanwhile, an Amnesty report reveals Conrad and over 1,000 detainees were convicted without fair trials.

“We call on the Cameroonian authorities to immediately and unconditionally release all those incarcerated for practising their rights to free speech and peaceful protest”, said Fabien Offner, Amnesty International’s Central Africa Researcher.

In a joint session held by the American Bar Association Center for Human Rights, the Committee to Protect Journalists and Freedom House, the coalition lamented how the press freedom and journalists’ safety has been declining for more than a decade. In most cases, the coalition complained, journalists are routinely attacked and imprisoned on anti-state, criminal defamation, false news, and/or retaliatory charges.

“Several journalists have been forced into exile, two journalists have died in government custody under suspicious circumstances since 2010, and, most recently, prominent journalist Martinez Zogo was murdered in January 2023,” a statement from the joint session reads. “Cameroon has appeared consistently on CPJ’s annual prison census since 2014, and it is among the worst jailers of journalists in Africa, behind Egypt and Eritrea.”

In fact in 2023, Reporters Without Borders described Cameroon as one of the dangerous countries for journalists in its world freedom index.

To ease the tension from the protest, the country’s president, Paul Biya, in 2019, pledged to convene a national dialogue to allow the government “examine the ways and means to respond to the deeply-held aspirations of the populations.” He also promised to pardon those involved in the protest.

At the national dialogue held last year, President Biya refused to show up. Notwithstanding, the President ordered the release of 333 prisoners and 102 arrested activists who opposed his reelection in 2018. While this appeared like a progressive gesture, many detainees, including Conrad, still continue to languish in prison.

Because of the President’s absence and his inability to deliver on his promise, Julius Ayuk Tabe, one of the detainees the Yaoundé military court sentenced to life behind bars, described the dialogue a “non event.”

The Freedom House’s report categorises Cameroon as “Not Free” after scoring 15 of 100, thanks to its repressive attitude to dissenting voices.

As hope seemed to fade within the borders of his country, Conrad calls on the international communities to intervene in addressing the systematic abuses of human rights and dissension of journalists. He hopes that since the American President Trump consistently rebuked the Cameroonian government for its abuse of the rule of law and violation of human freedom in his first term, “I am hopeful that he will continue to call out the Biya regime’s abuses in Cameroon,” he said.

From his prison cell, Conrad raises his hope high as his voice breaks through the prison bars. With Cameroon’s election approaching in October, he fears continued silence will only embolden the state and calls on the global community to defend press freedom and demand his release. The United Nations heard him.

“The appropriate remedy would be to release Mr. Conrad immediately and accord him an enforceable right to compensation and other reparations, in accordance with international law,” a statement by the United Nations Working Group reads.